The Making of an American

May 14, 2014 | by Edward White

Carl Van Vechten shaped and burnished the legend of Gertrude Stein.

This year marks the centenary of the publication of Tender Buttons,

Gertrude Stein’s collection of experimental still-life word portraits

split into the categories of objects, food, and rooms, and

which—excluding a vanity publication in 1909, which she paid for

herself—was the first of Stein’s work to be published in the United

States. Stein had hoped that this enigmatic little book would be her big

break, the thing to convince the American people of her genius. That

was not to be. Tender Buttons left critics bemused and made

barely a dent on the consciousness of the wider reading public. There

was no great clamor for more of her writing; Stein would have to wait

another twenty years to become a household name. Nevertheless, the

publication of Tender Buttons is now widely regarded as a

landmark in American literary modernism, the moment when one of the most

influential writers of the twentieth century first unfurled her

avant-garde sensibilities before the American public.

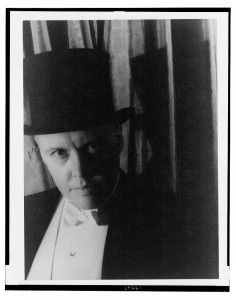

That moment would never have arrived had it

not been for the work of Stein’s most important champion, Carl Van

Vechten, the man who arranged for the book’s publication. Little

remembered today, Van Vechten was a pioneering arts critic, a popular

author of tart, brittle novels about Manhattan’s Jazz-Age excesses, an

acclaimed photographer, and a flamboyant socialite whose daring

interracial cocktail parties were a defining part of Prohibition-era New

York’s social scene. But his greatest legacy is as a promoter of many

underappreciated American writers, artists, and performers who went on

to gain canonical status. Names as diverse as Langston Hughes, Paul

Robeson, and Herman Melville all felt the effects of Van Vechten’s

boost. His first great cause was Gertrude Stein. He did more than anyone

else to carve her legend into the edifice of the American Century,

arranging publishing deals for her, photographing her, and publicizing

her work, a task he continued long after her death.

Stein knew how crucial Van Vechten was to

her career—not merely in the practical aspects of getting her work into

print, read, and discussed, but in helping create and disseminate the

mythology that surrounds her name. “I always wanted to be historical,

almost from a baby on,” Stein freely admitted toward the end of her

life. “Carl was one of the earliest ones that made me be certain that I

was going to be.” Van Vechten and Stein were strikingly different, led

wildly different lives. Hers was rooted in the domestic stability she

enjoyed with her partner Alice B. Toklas; his was an exhausting whirl of

binges, parties, and pansexual escapades. But they had two crucial

things in common: the conviction that Gertrude Stein was an irrefutable

genius and a love of mythmaking, an obsession with re-scripting reality

until they became the central actors in the fantastical scenes that

unfolded in their heads. When Stein played fast and loose with the facts

in her memoirs, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, many

were furious over her distortions. But Van Vechten understood that

telling the literal truth about her life—or anybody else’s—was never

Stein’s concern.

Indeed, one of those fabrications originated from an essay Van Vechten

himself had written, about his experience of the remarkable Paris

premiere of Le Sacre du Printemps two years earlier. That first

performance of Stravinsky’s taboo-busting ballet was a defining moment

in the emergence of modernism as an artistic force, and Van Vechten’s

ecstatic review of it has been cited over the last century as a key

eyewitness account of the event. But he never attended the first night:

he had failed to get tickets and had to content himself with the second

performance instead. Still, Van Vechten immediately understood the

epochal significance of the occasion. He decided he would not allow such

a trifling matter as the truth to prevent him from finding a place at

the center of events. Gertrude Stein happened to be in the audience with

Van Vechten for that second performance, and when he wrote her about

his deception, he breezily reassured her that writers such as they “must

only be accurate about such details in a work of fiction … I am not a

bit muddled about the facts.” Stein could not have agreed more.

In fact, she so approved of Van Vechten’s fiction that she embellished

the story further in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, suggesting that the first night of Le Sacre du Printemps

was also the occasion of their first meeting, and that after the

performance she rushed home to write a portrait of her new acquaintance.

Van Vechten and Stein had actually met in

that summer of 1913 at the Parisian townhouse Stein shared with Toklas.

Over the previous several months, Van Vechten, at this point a critic

for the New York Times, had developed a fascination with Stein

and her burgeoning legend—his friend, the shamanic Fifth Avenue salon

hostess Mabel Dodge, had given him a copy of the prose poem that Stein

had recently written about her, Portrait of Mabel Dodge at the Villa Curonia.

Van Vechten, always drawn to novelty and exoticism, was immediately

captivated by the thoroughgoing oddness of the writing, as well as the

tales he had heard about the deeply unconventional woman responsible for

it: a middle-aged Jewish lesbian in self-exile in France. On meeting

Stein for the first time he was thrilled to discover that she was every

bit as strange and marvelous as he had hoped she would be. He wrote his

lover back in New York about Stein’s charisma and intelligence, as well

as the delicious male nudes by Picasso that hung on her walls, some with

“erect Tom-Tom’s much bigger than mine.”

* * *

After that first meeting Van Vechten’s

interest in Stein swiftly morphed into an obsession. Back in New York he

set himself the task of hauling her from obscurity and into the

mainstream. Van Vechten’s encounter with this “cubist of letters,” as

she was described in a New York Times article he wrote about

her, came at a perfect moment for both of them. In the early months of

1913, many Americans got their first glimpse of artists such as

Kandinsky, Matisse, Picasso, and Duchamp when the Armory Show exhibition

of modern art hit New York with incendiary force. Stein’s links to

these European radicals—“freaks,” as at least one American newspaper

labeled them—generated much curiosity about her. Van Vechten, for his

part, was at the beginning of his journey as a Manhattan tastemaker,

loudly extolling the virtues of African-American theater, ragtime, and

modern dancers such as Isadora Duncan. In Stein he found the perfect

cause to champion: a unique artist whose mercurial work pulsated with

the spirit of the age, but also one whose public image he could shape

and bind himself to.

Early in February 1914, Van Vechten urged his friend and New York Times colleague Donald Evans to publish the manuscript of Tender Buttons through

his new publishing house, the Claire Marie Press. A thousand copies

were printed, but Evans suggested he did not expect them all to sell:

“There are in America seven hundred civilized people only” Claire

Marie’s brochure claimed, and it was “civilized people only” that the

company said it was interested in reaching, which begs the question of

whom exactly the remaining three hundred books in Tender Buttons’s

print run were intended for. Of Stein’s work, Evans said that “the

effect produced on the first reading is something like terror.” It was

an unconventional means of promotion—but one that ensured Stein remained

the very image of the aloof literary genius.

Van Vechten did a better job of bringing

Stein’s writing to public attention with an article, “How to Read

Gertrude Stein,” published in the fashionable arts magazine The Trend

in August 1914. As the double meaning of the title suggests, it was

intended to be an insider’s guide to understanding Stein’s work as well

as her personality, framing Van Vechten as the man with an all-access

pass to the great enigmatic genius of the age. Always a more assured

critic of music than of literature, Van Vechten turned to musical

referents for his most effective explanations of Stein’s writing, a

tactic that countless others have followed in the intervening century.

“She has really turned language into music,” he asserted; “Miss Stein

drops repeated words upon your brain with the effect of Chopin’s B Minor Prelude.”

The article also helped to develop and solidify Stein’s image as a

guru-like figure, the sort of character Jo Davison would capture in his

famous sculpture of Stein as Buddha some years later. “As a personality

Gertrude Stein is unique,” Van Vechten wrote. “She is massive in

physique, a Rabelaisian woman with a splendid thoughtful face; mind

dominating her matter.” Stein wrote her charge to let him know that she

was “very well pleased with your article about me.”

Considering Van Vechten’s hero-worshipping

of Stein, it was more than a little strange for them both that over the

next dozen years she remained a cult figure while his fame and

importance soared—as a critic and a novelist, but most crucially as a

trendsetter and the premier white promoter of the Harlem Renaissance.

Success and celebrity never dampened his ardor for Stein, though, and he

worked tirelessly on her behalf. In 1922 he came close to convincing

Alfred A. Knopf to publish Stein’s Making of Americans, and

references to her writing suffused his own literary efforts, which

always attempted to frame Stein as the most important author of her

generation, the light source from which all modern American writers took

their nourishment. He even found opportunity to crowbar Stein into the

heart of his infamous 1926 bestselling novel about the lives of

African-Americans in Harlem, Nigger Heaven—a mind-blowingly

insensitive title that caused every bit as much offence to black people

then as it would now. The novel’s heroine is Mary Love, a young black

woman with a passion for literature and European history, but who

struggles to connect with what Van Vechten characterizes as her innate

blackness, her “heritage of rhythm and warmth.” Accordingly, Mary

develops an obsession with Gertrude Stein’s depiction of the black

experience in “Melanctha,” Stein’s novella about an African-American

woman from Baltimore. In fact, Mary has committed great chunks of the

book to memory, and Van Vechten dedicates a page-and-a-half to her

recitation of a particular passage. It is a preposterous moment in an

often bizarre novel, but nothing better reflects Van Vechten’s fealty.

Publicly and privately, Van Vechten lavished Stein’s work with praise,

but in thirty-three years of friendship, Stein never returned the

compliment. The mountains of letters the two swapped over the decades

clearly show that Stein’s affection for Van Vechten was genuinely deep,

but her faint praise for his literary work is hugely conspicuous. “What

you have done is very clear and I like it” was her tepid response to Van

Vechten’s novel The Blind Bow-Boy, widely thought to be his finest moment as a novelist. It was the most effusive she ever got about his work.

In almost all of his friendships, Van

Vechten liked to assert himself as the senior partner, a bossy

proprietorial force of nature who dazzled and bulldozed with wit and

charisma. Yet with Stein, whose singular genius he never doubted, he was

happy to play the supplicant; at her he never lashed out or sulked as

he did with so many others when he felt his specialness was being

ignored. It was the reason that the two of them were able to maintain

such a happy relationship for so many years. Ernest Hemingway once noted

that Stein could never remain friends with anybody whom she saw as a

threat. Van Vechten, a man she considered a literary lightweight and who

was forever vociferously renewing his oath to her, was about as far

from a threat as it was possible for her to imagine. Whenever Stein and

Toklas executed one of their periodic culls of friends and groupies, Van

Vechten, singing Gertrude’s praises thousands of miles away in his

Manhattan bubble, avoided the blade.

* * *

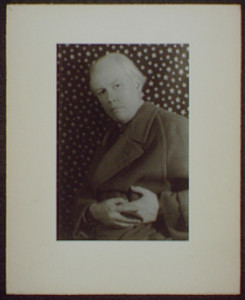

By the start of the 1930s, Van Vechten,

rich and bloated from what he termed “the splendid drunken twenties,”

had given up writing and taken up portrait photography, spending days on

end locked away from the unpleasant realities of Depression-era America

surrounded by prints of his beautiful and celebrated subjects. He shot

an astonishing array of noteworthy people, from George Gershwin to

Georgia O’Keeffe. When The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas

became an unexpected bestseller in 1933, Van Vechten became impatient to

add her picture to his gallery. The suddenness of Stein’s success

surprised Van Vechten as much as anyone. Almost the moment her book hit

the shelves she morphed from a cult figure into a bona-fide celebrity.

Fulsome reviews by prominent writers appeared everywhere, and a

photograph of her taken by one of her new favorite courtiers, George

Platt Lynes, graced the cover of Time. Van Vechten was thrilled

for her—but bitterly jealous, too. He feared that in the frenzy of

acclaim, he would be pushed from the frame at the expense of new,

younger disciples.

The chance to link himself definitively to

Stein in this phase of her career came in the fall of 1934, when she

arrived in the United States for her triumphant homecoming lecture tour.

Van Vechten was partly responsible for instigating and arranging the

tour, and he provided invaluable assistance in soothing her nerves and

cooing praise into her ears, reassuring her that her time had come; the

American public really was crazy for her at last. He saw the proof

himself as he followed Stein to many of her engagements across the

country—striding around the stage with her hands in her pockets, she

charmed audiences with a beguiling mixture of esotericism and folksy,

homespun wisdom. To some she seemed like an adorably eccentric

grandmother; to others, a radically prophetic voice. To just about

everyone she was as enchanting as the woman Van Vechten had first met in

Paris in 1913.

When he got the chance to photograph Stein

during her tour, Van Vechten made sure he did so in a way that took her

public image to a new level of grandeur. In Virginia, he shot her in

front of neoclassical buildings, including the Rotunda designed by

Thomas Jefferson, deliberately placing her within the pantheon of

historic American heroes. Once again their shared instinct for myth

creation kicked in; they both understood that this was the moment in

which Gertrude Stein would achieve her immortality. Touring America, she

saw the history of the nation more vividly than ever before, and she

sensed her place within it. When she passed through Dayton, Ohio, she

noted to Van Vechten that this was where the Wright Brothers had started

out; Marion, Ohio, she learned excitedly, was Warren Harding’s

hometown. From Illinois she wrote Van Vechten breathlessly, urging him

to “make a pictorial history of these United States and I will write one

and we will all be so happy.”

By now, Stein’s letters to Van Vechten were routinely addressed to

“Papa Woojums,” Woojums being the name of the family unit that Stein,

Toklas, and Van Vechten created for themselves around this time, and in

which each adopted a distinct role. While Van Vechten and Toklas were

the parental figures—Toklas was “Mama Woojums”—Stein was “Baby Woojums,”

not because she was helpless or vulnerable but because she was special,

a treasured jewel who needed coddling and directing lest her savant

genius go to waste. It was a subtle but telling reconfiguration that

recognized Van Vechten’s talents and satisfied his self-image as a man

of importance—yet still ensured that Stein remained the center of

attention.

The night before Stein sailed back to

France, Van Vechten had her come over to his apartment for a final photo

shoot. In his cramped makeshift studio, he positioned her in front of a

crumpled and ragged Stars and Stripes, as if the flag was being blown

about in a strong breeze. This was not a Gertrude Stein that had ever

been seen before; not a Delphic oracle or a bohemian eccentric, but a

pillar of the establishment. With a firm, unsmiling gaze and the haircut

of a Roman senator, Stein had been transformed by Van Vechten’s lens

into something permanent, weighty, and emphatically American, like a

female addition to Mount Rushmore. Van Vechten’s mission to embed

himself in Stein’s public profile was complete. The photograph has

become perhaps the definitive image of Stein, and when a book of her

lectures was published shortly after the tour, it was this photograph

that adorned its front cover, chosen by Stein herself.

When Stein died in 1946, it was to Papa

Woojums that she left the task of getting her large number of

unpublished manuscripts into print, the measure of her respect and

affection for him. Despite fearing that “Gertrude had bitten off more

than I could easily chew,” Van Vechten faithfully undertook his duty.

Within a little more than a decade, Stein’s complete works had been

published.

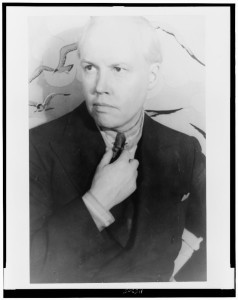

Edward White is the author of The Tastemaker: Carl Van Vechten and the Birth of Modern America.

White studied European and American history at Mansfield College,

Oxford, and Goldsmiths College, London. Since 2005 he has worked in the

British television industry, including two years at the BBC, devising

programs in its arts and history departments. He is a contributor to The Times Literary Supplement. He lives in London.

No comments:

Post a Comment