April 17, 2013

|

Behind the Scenes,

Conservation,

Jackson Pollock Project

MoMA’s Jackson Pollock Conservation Project: Insight into the Artist’s Process

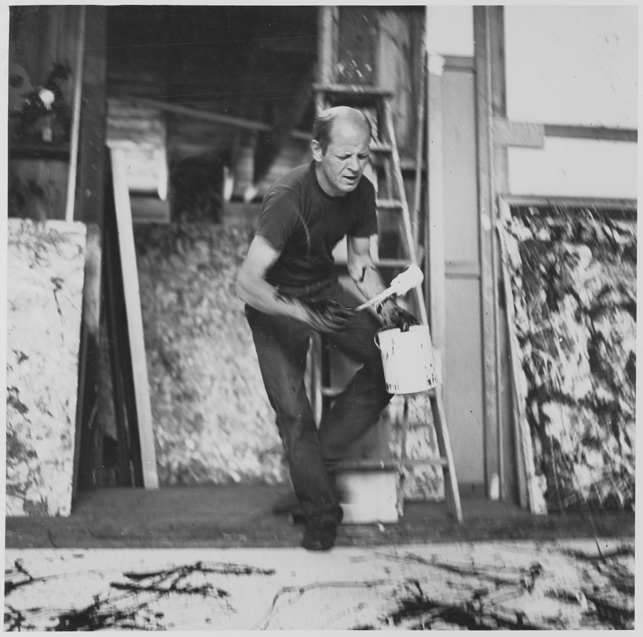

Jackson Pollock at work in his studio, 1950. Photo: Hans Namuth

Thus far, our Pollock blogging has focused primarily on how conservators assess the condition of and treat a work of art. In addition to caring for the Museum’s collections, though, MoMA conservators frequently pursue technical art historical inquiry to clarify curatorial questions and better understand artists’ material choices and working methods. The Pollock project has been one such opportunity to fill some of the gaps in the popular narrative established by Namuth’s now-iconic photographs.

Questions regarding Pollock’s choices and technique may be investigated through primary source documentation such as photographs, artist’s statements, and first-hand accounts. We gather these resources, and illuminating information can be gleaned from them. However, they are ultimately limited, with accounts of art-making captured in an isolated instant, edited by ego, or filtered through memory.

In the conservation studio, we have access to an additional, crucial resource: the work of art itself, in this case Pollock’s paintings. In one of our earlier posts, we looked closely at One: Number 31, 1950 and noted several surface effects that Pollock was able to achieve. Now, let’s explore some of these observations more thoroughly.

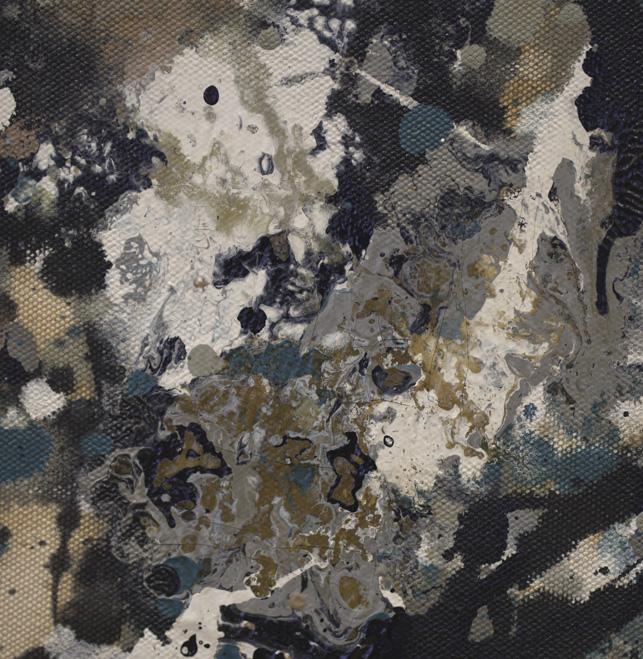

As we’ve covered One’s surface inch by inch, first in looking, then in cleaning, we’ve become intimately acquainted with the paints and other materials to be found there. In the 1950 murals, Pollock moved decisively away from the densely worked surface of late 1940s paintings like Full Fathom Five (1947).

Jackson Pollock. Full Fathom Five.

1947. Oil on canvas with nails, tacks, buttons, key, coins, cigarettes,

matches, etc. Gift of Peggy Guggenheim. © 2013 Pollock-Krasner

Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

![Pours of black and aluminum paint crisscross an underlayer of thick, white brushwork. An embedded paint cap can be seen just up and to the left of center]](http://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/inside_out/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/FFF_detail.sm_.jpg)

Pours

of black and aluminum paint crisscross an underlayer of thick, white

brushwork. An embedded paint cap can be seen just up and to the left of

center

Jackson Pollock. One: Number 31, 1950.

1950. Oil and enamel paint on canvas. Sidney and Harriet Janis

Collection Fund (by exchange). © 2013 Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists

Rights Society (ARS), New York

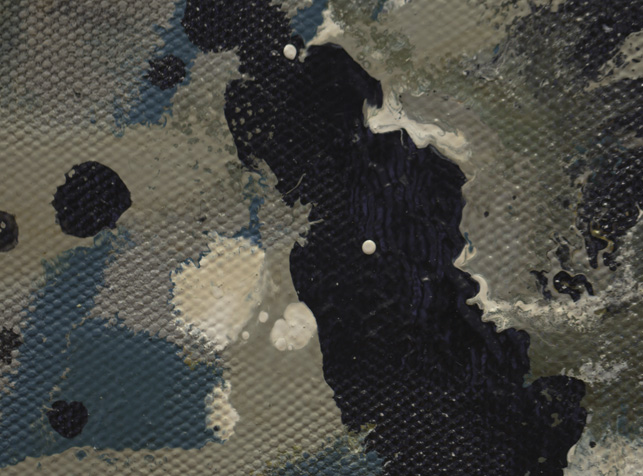

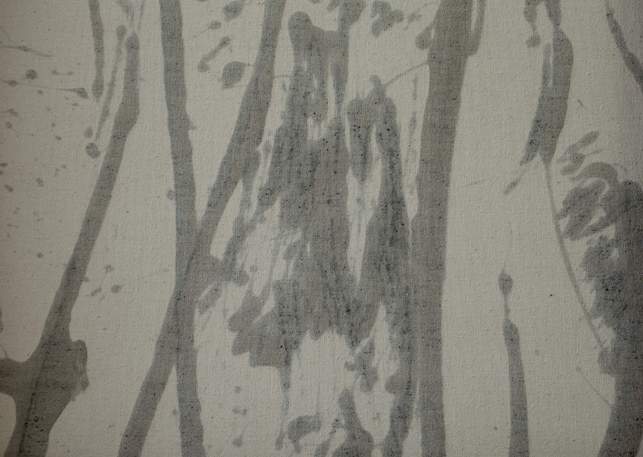

The few, scattered spots of bright yellow artist’s oil paint stand out against One’s subdued palette of enamel paints

Pollock

thinned his paints to achieve a range of consistency. Here, diluted

paints seep into the canvas, staining it with pigment

Unlike the cigarette, key, handful of tacks, and other found materials embedded in the surface of Full Fathom Five, the inclusions we found in One appear to be a mark of Pollock’s process and chance rather than deliberately placed elements. The bits of wood that dot the uppermost white layer could be remnants of a stick that Pollock was using in lieu of a paintbrush, or, like the fly that came to rest in this passage of black, they may just be the detritus that comes with working on the floor of a barn.

Scattered

small bits of wood can be seen, primarily in a white paint that appears

to be one of the final layers that Pollock applied

A housefly met his end in a pour of black paint

The translucent gold-amber substance is cured, concentrated medium

Typical wet-into-wet paint mixing. Notice how the edges of the colors flow into each other

Compare

the blending (above, to the left, etc.) to the hazy swirl of multiple

colors achieved by generous amounts of paint thinner

A series of uniform, brown drips deliberately follows a black passage of paint

A few scattered pink drips, in contrast, appear more likely to be the result of random studio accidents

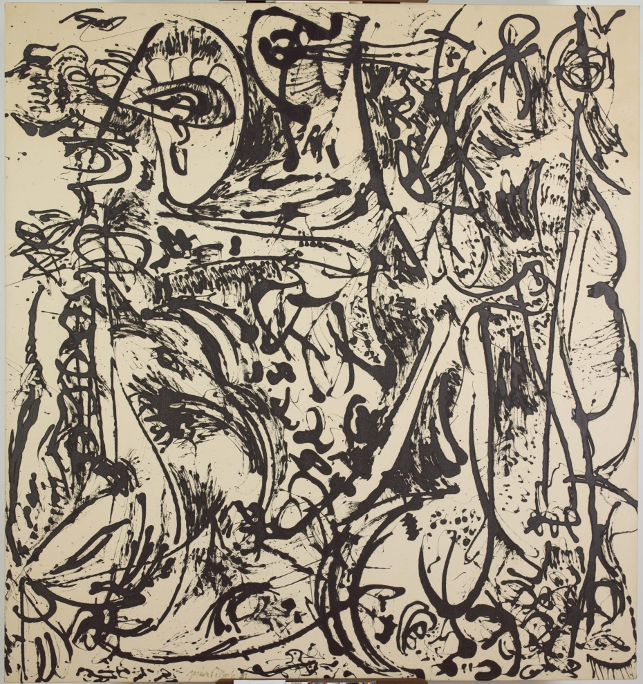

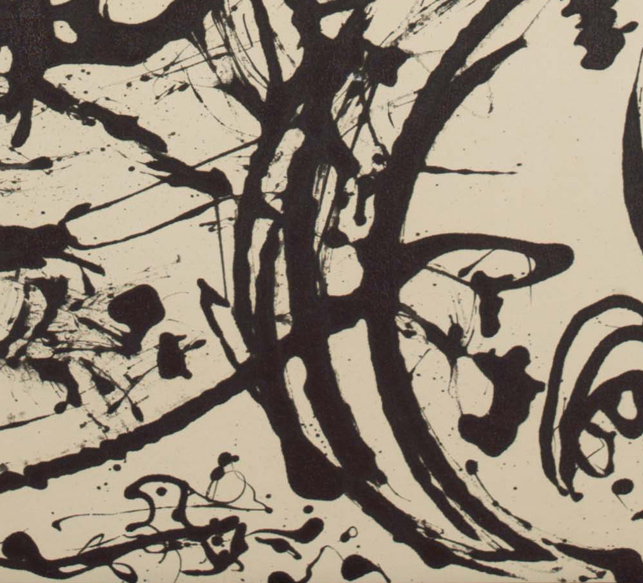

And this deliberate control of his paint appears to have increased as Pollock moved into the black-and -white paintings of 1951. Pollock pared down his palette and, in composing Echo: Number 25, 1951, his mark-making as well.

Jackson Pollock. Echo: Number 25, 1951.

1951. Enamel paint on canvas. Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss

Bequest and the Mr. and Mrs. David Rockefeller Fund. © 2013

Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

When looking at the back of Echo, thin, interior lines can be seen that correspond to the broader paint marks

Viewed from the front, the lines of paint exhibit a pulsating quality, the result of Pollock’s tools and technique

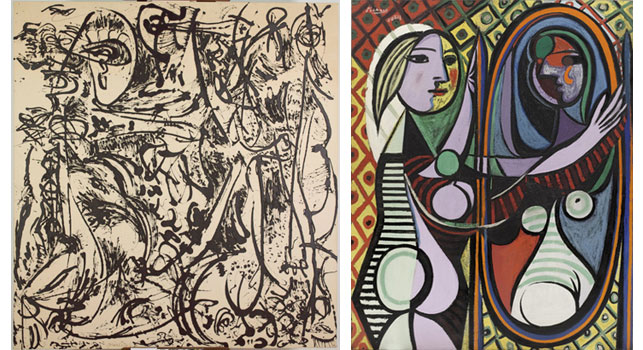

Finally, much has been discussed about the extent and nature of Pollock’s return to recognizable imagery in his work, and dissecting Echo’s composition reveals elements of familiar images from the artist’s early sketchbooks. Another telling parallel can be drawn between Echo and Pablo Picasso’s Girl Before a Mirror (1932). The close parallels reveal that Pollock’s fascination and competition with Picasso continued even at the later stages of his career. Notice the compositional similarities between the two works. Compare the head, eye, outstretched arm, and belly of Picasso’s Girl to the analogous forms in Echo. Might the crosshatching we see in Pollock’s painting represent a shorthand for the diamond-patterned background of Girl?

From left: Jackson Pollock. Echo: Number 25, 1951.

1951. Enamel paint on canvas. Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss

Bequest and the Mr. and Mrs. David Rockefeller Fund. © 2013

Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Pablo

Picasso. Girl Before a Mirror. 1932. Oil on canvas. Gift of Mrs. Simon Guggenheim. © 2013 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

No comments:

Post a Comment