|

Dorothea Lange Torso, San Francisco, 1923 Gelatin silver print, 13½ x 10½ inches

Dorothea Lange

Torso, San Francisco, 1923

Gelatin silver print, 13½ x 10½ inches

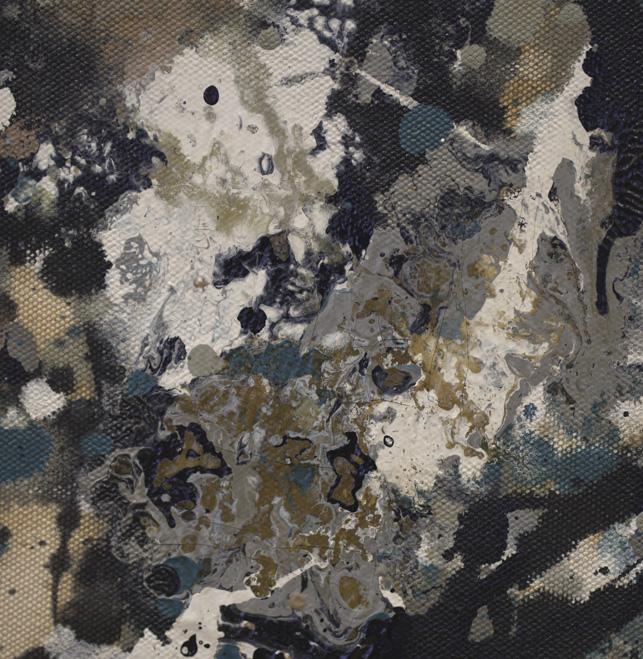

![Pours of black and aluminum paint crisscross an underlayer of thick, white brushwork. An embedded paint cap can be seen just up and to the left of center]](http://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/inside_out/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/FFF_detail.sm_.jpg)

In

the undergraduate history of English course I am teaching this term, I

request/require that the students teach me two new slang words every day

before I begin class. I learn some great words this way (e.g., hangry “cranky or angry due to feeling hungry”; adorkable

“adorable in a dorky way”). More importantly, the activity reinforces

for students a key message of the course: that the history of English is

happening all around us (and that slang is humans’ linguistic

creativity at work, not linguistic corruption).

In

the undergraduate history of English course I am teaching this term, I

request/require that the students teach me two new slang words every day

before I begin class. I learn some great words this way (e.g., hangry “cranky or angry due to feeling hungry”; adorkable

“adorable in a dorky way”). More importantly, the activity reinforces

for students a key message of the course: that the history of English is

happening all around us (and that slang is humans’ linguistic

creativity at work, not linguistic corruption).1. Does anyone care if my cousin comes and visits slash stays with us Friday night?

2. I have been asking everyone I know in the Chicago area if they’re going slash if they’d willing [sic] to let me tag along slash show me around because frankly I’d have no idea how to get around Chicago on my own

3. … culminating in Friday’s shootout-slash-car-chase-slash-manhunt-slash-media-circus around the apprehension of the bombing suspect.

4. I spent all day in the UgLi [library] yesterday writing my French paper slash posting pictures of cats on my sister’s Facebook wall.

5. I went to class slash caught up on Game of Thrones. [I made sure to clarify that this was not in reference to our class!]

6. I need to go home and write my essay slash take a nap.

7. I really love that hot dog place on Liberty Street. Slash can we go there tomorrow?

8. Has anyone seen my moccasins anywhere? Slash were they given to someone to wear home ever?

9. I’ll let you know though. Slash I don’t know when I’m going to be home tonight

10. so what’ve you been up to? slash should we be skyping?

11. finishing them right now. slash if i don’t finish them now they’ll be done in first hour tomorrow

12. JUST SAW ALEX! Slash I just chubbed on oatmeal raisin cookies at north quad and i miss you

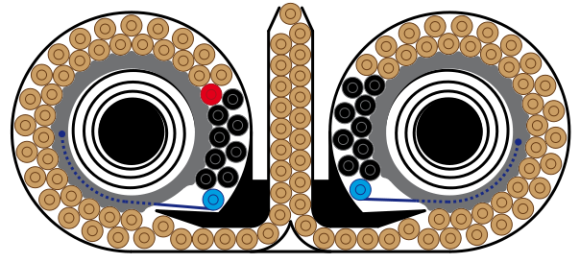

any “destructive device” defined as any explosive, incendiary, or poison gas – bomb, grenade, rocket having a propellant charge of more than four ounces, missile having an explosive or incendiary charge of more than one-quarter ounce, mine, or device similar to any of the devices described in the preceding clausesThat includes a pressure-cooker Internet-recipe bomb that killed 3 people and injured many more. But why is a version of an AR-15, as used by Adam Lanza, that killed 28 human beings, not treated the same way? Why was that act not treated as a suicide bombing would be? If something that kills three people is responsible for “mass destruction”, why not a military weapon that can kill 28 and end in suicide? The AR-15 can be adapted to have a hundred bullets in a Beta C-Mag magazine. Here’s a fantastically phallic drawing of how many bullets can be fired:

any weapon that is designed or intended to cause death or serious bodily injury through the release, dissemination, or impact of toxic or poisonous chemicals, or their precursors

any weapon involving a biological agent, toxin, or vector any weapon that is designed to release radiation or radioactivity at a level dangerous to human life

Theology and texts have far less power over shaping a religion’s lived experience than intellectuals would like to credit… On many specific issues I agree with Rod Dreher a great deal when it comes to Islam. I do think too many Muslims and their liberal fellow travelers attempt to squelch justified critique of the religion by making accusations of bigotry (I’m on the receiving end regularly). Obviously I disagree with that. But, where I part with Rod is his “theory of religion.”I wonder if Tamerlan Tsarnaev or Richard Reid believed that Muhammed has little to do with Islam. I’m not talking about an intellectual grasp of theological nuances. I’m talking about a text that, unlike the Gospels, is asserted to have been directly given by God through Muhammed with no human intervention or error. And I’m talking about a religious genius who wielded temporal power from the get-go. Jesus accepted powerlessness in the face of Roman imperialism. Muhammed? As Khan notes,

As a religious believer with a deep intellectual predisposition I doubt Rod Dreher and I will be able to agree on the primal point at issue. Not only do I believe that the theologies of all religion are false, but I believe that they’re predominantly just intellectual foam generated from the churning of broader social and historical forces. Some segments of the priestly class will always find institutional politics exhausting, mystical experience out of their character, and legal commentaries excessively mundane. These will be drawn to philosophical dimension of religious phenomena. Which is fine as far as it goes, but too often there is an unfortunate tendency toward reducing religion to just this narrow dimension. But I have minimal confidence that most people will accept that the Christianity church has little to do with Jesus and that Islam has little to do with Muhammad. And yet I think that’s the truth of it….

Muhammad was his own Constantine. That is, he was not simply a spiritual teacher, but also a temporal ruler. More broadly, while Christianity became an imperial religion, Islam was born an imperial religion.And it seems strange to me that that early, critical fact has not had an impact on Christianity’s eventual ability to disentangle itself from worldly territorial power and on Islam’s inability to do so. Jesus allowed himself to be crucified by power. Muhammed was an expansionist conqueror, who waged war for territory. I do not believe, as Khan does, that those two facts are irrelevant to the manifestations of Christianity and Islam today – especially in their compatibility with secular government.

Much of Andy Warhol’s work, including work incorporating appropriated images of Campbell’s soup cans or of Marilyn Monroe, comments on consumer culture and explores the relationship between celebrity culture and advertising.Still, the appeal leaves it to the lower court to decide just how much an artist needs to affect an image in order to change it. There are still five photographs the court has refused to judge (Graduation, Meditation, Canal Zone (2007), Canal Zone (2008), and Charlie Company)–because their alterations are so small. They write of those images:

While the lozenges [in Graduation], repetition of the images, and addition of the nude female unarguably change the tenor of the piece, it is unclear whether these alterations amount to a sufficient transformation of the original work of art such that the new work is transformative.And, when it comes down to it, that’s a question of whether, and for whom, these are effective works of art.