Friday, March 29, 2013

Yep. Good news

“I’m a Christian not because of the resurrection … and not because I think Christianity contains more truth than other religions … and not simply because it was the religion in which I was raised (this has been a high barrier). I am a Christian because of that moment on the cross when Jesus, drinking the very dregs of human bitterness, cries out, “My God, my God, why hast Thou forsaken me?” … The point is that he felt human destitution to its absolute degree; the point is that God is with us, not beyond us, in suffering,” – Christian Wiman.

Thursday, March 28, 2013

Art Review

A Young Colorist, Antennas Aquiver

Helen Frankenthaler, at the Gagosian Gallery

Richard Perry/The New York Times

Painted on 21st Street “Untitled” (1951), in a show at Gagosian on Helen Frankenthaler’s early period. More Photos »

By ROBERTA SMITH

Published: March 21, 2013

On Oct. 26, 1952, a 23-year-old artist named Helen Frankenthaler

made a painting on unstretched, unprimed canvas laid on the floor,

using a freehand stain technique that owed a great deal to Jackson

Pollock but was less systematic. She called it “Mountains and Sea,” and

it became her best-known, most influential work. Its bounding scale,

skirmish of pastel colors and charcoal lines, and mixture of landscape,

still life and abstraction were distinctive. But most important was the

way it fused color and canvas into a new, streamlined unity.

Frankenthaler’s stain painting method, as it was sometimes called, was

considered a breakthrough in many circles, the gateway to what would

become Color Field abstraction.

Multimedia

Art historically, “Mountains and Sea” was something like Frankenthaler’s

15 minutes of fame, but generally almost nothing is known about where

it came from. “Painted on 21st Street: Helen Frankenthaler From 1950 to 1959,”

at the Gagosian Gallery in Chelsea, performs the useful service of

setting it firmly in the context of the 1950s, the best decade of the

artist’s career. Here “Mountains” becomes the pivot between the

all-but-unknown work that preceded it and a lavish, refreshing display

of the various if more familiar kinds of wild beauty that it unleashed

in subsequent paintings.

Fabulously enlightening and unruly, this show of 29 paintings is the

latest example of the historical excavations with which Larry Gagosian,

the art dealer everyone loves to hate, regularly redeems himself. He may

have a deleterious inflationary effect on the art market and the

careers of younger talents and nontalents, but his shows of older, often

nonliving artists would do any museum proud. This one has been

organized in cooperation with Frankenthaler’s estate by John Elderfield,

chief curator emeritus of painting and sculpture at the Museum of

Modern Art. (Its richly illustrated catalog is distinguished by Mr.

Elderfield’s thoughtful essay and Lauren Mahony’s wonderfully detailed

chronology of Frankenthaler’s passage through the 1950s, built around

her letters, exhibitions and reviews.)

Frankenthaler was Color Field’s prodigy and its single-minded glamour

girl. Born into a wealthy family in Manhattan, she grew up cosseted,

cultured and bent on painting. She attended the Dalton School, where her

art teacher was the Mexican painter Rufino Tamayo, and went on to Bennington College in Vermont, studying with the painter Paul Feeley.

Graduating in 1949, Frankenthaler returned to New York and set up her

first studio on East 21st Street. She soon began an affair with the

esteemed art critic Clement Greenberg, nearly 20 years her senior, with

whom she frequented galleries and museums, visited artists’ studios and

traveled abroad. It is a tribute to Frankenthaler’s intelligence and

ambition that she was soon up to speed on the latest innovations of the

New York School, in addition to becoming friendly with many of its

leading lights, including Pollock and David Smith.

Sometime in 1953 Greenberg brought Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland, two

painters from Washington, to Frankenthaler’s studio, to show them

“Mountains and Sea” — in all likelihood when Frankenthaler was not

there. (Anyone irked by the presumption of this, raise your hand.) The

Washington visitors immediately grasped the implications of

Frankenthaler’s singing, thinned-down colors and the way they sank into

the unprimed canvas. Louis later described “Mountains and Sea” as “the

bridge between Pollock and what was possible.”

The rest, you could say, is mystery. Frankenthaler’s stained-color

technique has often been treated like a bit of precocious luck that

Morris and Louis adapted and developed. Besides, Color Field’s critical

prestige, if not its market share, began to contract after 1960, the

year Frankenthaler was given a survey at the Jewish Museum. Frank

Stella, a young artist fresh out of Princeton, had already emerged as

the next hot thing, and Minimalism was on the horizon.

Frankenthaler’s path to “Mountains and Sea” deserves to be an immutable

part of postwar history, and this show should make it so. It conjures a

vivid portrait of the artist as a fearless young woman, unencumbered by

rules or ideology, who had a remarkable ability to bend other artists’

styles and motifs to her own expressive needs. One advantage was her

restless attention to the methods and materials of both painting and

drawing, which she tended to combine.

This is evinced by the works in the show’s revelatory opening gallery,

starting with the caked, episodic surface of “Painted on 21st Street”

(1950), a smeary white-on-white mixture of paint, plaster, sand and

scribbled fragments that suggests a pristine cave painting.

Another surprise is “The Sightseers,” a youthful masterpiece from 1951

in enamel and crayon on paper mounted on Masonite. After establishing an

open fretwork of looping black lines, Frankenthaler fills the

interstices with bright crayon, applied in broad areas accented with

sharp scribbles and all kinds of marks and signs. There are periodic

glimpses of “sights”: seascapes, mountains, possible figures, a crown.

“The Sightseers” evokes precedents including Pollock, Krasner, de

Kooning’s great “Excavation”

and maybe a little Jean Dubuffet, yet it radiates an assured

independence, partly because of the eccentric way it is made.

The same goes for the “Untitled”

from 1951, a kind of landscape of tan ground and turquoise sky

populated by a screenlike parade of who knows what — multicolored

aircraft? sea creatures? plants? — accented once more with the

fragmented black lines. Look closely, and you’ll see early signs of the

stain technique among several other manipulations of paint. Here Miró

and Gorky join the list of possible inspirations. Around the corner, the

raucously exuberant “Ed Winston’s Tropical Gardens,” with its bright

yellow ground and intimations of plants, trees and fruits, might be a

billboard honoring Gorky’s “Garden in Sochi.”

Mr. Elderfield argues that Frankenthaler was more a second-generation

Abstract Expressionist than a Color Field painter, especially in the

1950s, and this show bears him out. He also rightly contends that

subject matter was essential to her art. It helped that she was as

acutely attuned to the natural landscape as she was to the culture of

painting. And while most members of the second generation cleaved to de

Kooning, Frankenthaler concentrated on Pollock, combining aspects of his

early and late phases, when he was most involved with imagery and myth.

Her best works are a kind of swirling, centrifugal mix of form, process,

possible meaning and gorgeous, unpredictable colors, shot through with

joie de vivre and wit. She wanted her paintings to seem quickly made and

to be seen all at once. Yet they sustain concentrated looking, and

reward time spent taking them apart and putting them back together, as

they slip between legibility and abstraction, control and abandon, lines

and seeping forms.

Frankenthaler gave herself a tremendous amount of permission. In

“Western Dream,” of 1957, you can almost hear her naming the various

motifs as her hand produces them: red insect, black idol, blue vortex,

desert sand. In “Europa” she reiterates Titian’s straining goddess as a remarkably accurate blob of bright pink and then crosses it out, as if dissatisfied. In “Before the Caves,”

she festoons an orange foot-shaped peninsula with lavender, gray and

red and squeezes it between feathery curving lines that whip in from the

sides.

Frankenthaler refused to see herself as a “woman painter,” although

feminist art historians would later draw parallels between her staining

technique and menstrual flow. (The insouciant, almost mocking 1952

“Scene With Nude” — with its tiny splatters of red paint between the

outlines of female legs — provides some reason for doing so.) But her

sense of freedom is to some extent implicitly female. Any woman making

art at Frankenthaler’s level in the 1950s did so, at least in part, from

a necessary sense of defiance. It burns bright in these canvases.

“Painted on 21st Street: Helen Frankenthaler From 1950 to 1959”

remains on view through April 13 at the Gagosian Gallery, 522 West 21st

Street, Chelsea; (212) 741-1717, gagosian.com.

Wednesday, March 27, 2013

Like it or leave it

A History of Like

The marketing field has long been obsessed with likability, but Facebook may be inadvertently revealing how shallow our liking goes

If you blog, run a university home page, do e-commerce, write news articles for a local paper, have a local government site, or do nearly anything with the Internet, you’re pretty much required to have users “like” your pages. Otherwise, you’re going to be left out of the new economy of quantified affect. We live in what Carolin Gerlitz and Anne Helmond call a Like Economy, a distributed centralized Web of binary switches allowing us to signal if we like something or not, all powered by the now ubiquitous Facebook “Like” button.

But why “Like”? Why not “Love,” or “I agree,” or “This is awesome”? At first it seems like one of those accidents of popular culture, where an arbitrary boardroom decision eventually dictates our everyday language. In fact, one history of Facebook’s Like button presents it in these very terms: Facebook engineer Adam Bosworth noted that the button began as an Awesome button but was later changed to Like because like is more universal. If it had stayed Awesome, perhaps we’d be talking about an economy of Awesomes binding together the social Web and we would sound more like Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles than Valley Girls.

There’s a deeper history to “like,” though, that is far older than Facebook. The marketing subfield of Liking Studies, which began before Internet use became mainstream, is key to understanding how this somewhat bland, reductive signal of affect became central to the larger consumer economy we live in. It’s also explains why Facebook will never install a Dislike button.

***

What’s the best way to predict whether an advertisement increases

sales or not? The marketing field has searched for the answer to this

question for decades. (If I knew, I would be the head of some unctuous

marketing firm instead of a state employee.) In the early 1990s, the

Advertising Research Foundation’s (ARF) “Copy Research Validity Project”

proposed a simple answer: the advertisement is “likable.” The massive

study compared pairs of television ads in various settings and methods,

against a wide range of accepted marketing measures: persuasive

elements, how well the advertisement is recalled afterword, the clarity

of the message, and (seemingly as an afterthought) how well the ad was

“liked.”Of all the measures, “likability” was the surprise winner. “The average impression of the commercial, derived from a five-point liking scale, picked sales winners directionally 87 percent of the time and had an index of 300 (i.e., picked winners and was significant 60 percent of the time).” In other words, you like, you buy.

As the authors of the report, Russel Haley and Allen Baldinger, explain, “It appears probably that ‘liking’ is what Gordon Brown has called a ‘creative magnifier’ for both persuasive messages and for messages that are recalled.” Likable ads, they conclude, are more persuasive and memorable than others. This triggered the development of Liking Studies, as academic and practicing marketers set out to further refine the contours of liking as an ad-copy-test measure.

Liking studies further decomposed likability into cognitive and affective elements. On the cognitive side, researchers theorized that viewers who like an ad pay attention and thus recall its message better. In terms of affect, a 1994 study by David Walker and Tony M. Dubinsky in the Journal of Advertising Research explores a “theory of ‘affect transfer,’” which “asserts that if viewers experience positive feelings towards the advertising, they will associate those feelings with the advertiser or the advertised brand.” A likable ad thus promises to encode brands into our bodies as pre-cognitive desire.

Of course, affect and cognition are complex phenomena. To be fair to academic marketers, there are repeated calls in the advertising research literature to resist reducing this complexity to liking and, at the very least, to continue to use other copy-testing measures in addition to likability to predict an ad’s success. However, the underlying complexity of cognition and affect actually reinforces the value of likability as a measurable aspect of ads. The value of like is that it abstracts and condenses the complex thoughts and emotions it contains and, like any good abstraction, provides a simple and commensurable quantification of complexity. If a test subject says, “I like this ad!” it seems to stand in for the less cut-and-dried aspects of recall and emotion.

For a largely empirical, positivist field such as marketing – which has pretensions of being a science, not an art –independent variables such as likability have value because of their perceived universal predictive power. With globalization, marketing is in greater need of just such a universal measure capable of predicting the success of global branding campaigns across cultural contexts. Cultural variations might change how marketers go about getting us to like brands, but the goal is always likability.

One vertigo-inducing marketing moment illustrates this well. Since 1989, USA Today has published metrics on the most well-liked Super Bowl ads. These metrics partly inspired the makers of FedEx’s 2005 “Perfect” Super Bowl ad, which combined the top 10 likeable elements of previous Super Bowl ads. (It featured Burt Reynolds getting kicked in the nuts by a dancing bear while a cute kid and sexy cheerleaders looked on. The bear talked to Reynolds about Smokey and the Bandit after Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believing” played. Oh, and somewhere in there is a message about how effective FedEx is at delivering things.) After this ad proved quite likable, the academic authors of a 2013 study of Super Bowl ad likability used many of its elements to measure the likability of other Super Bowl ads in the 2000s. Their discovery: animals, cute kids, and humor are all elements of a likable ad. Their study also used data from, where else, USA Today‘s Ad Meter likability measures. This self-referential loop will likely sentence us to ads featuring animals, cute kids, and bad humor for the rest of our Super Bowl watching lives.

***

Or maybe not. We are now allowed, even expected, to like other things

than what’s sold in Super Bowl ads. If you read even only the first two

sentences of any given marketing paper today, you invariably learn that

we are living in a new age where the user is in control. Social media

in general, and Facebook in particular, are supposedly driving a

brand-new world where marketers, editors, and other gatekeepers are

marginalized and mass culture is dissolving into niche cultures and

individual expression.But if we keep the history of marketing in mind, including the development of Liking Studies, we see how Facebook is caught up in longer histories, specifically the history of the desire to dissect, study, and recompose a particular subject, the sovereign consumer.

Facebook’s Like button has been lauded as a radically democratic tool allowing users to finally make their opinions heard, but the marketing field has always regarded the sovereign consumer’s opinions the most important element in the circuit of production. After all, sovereign consumers realize the value locked away in commodities: when they buy, the corporation gets paid. In order to have us be better value-realization machines, marketers know they need to know what we like. The Like button is a logical extension of the studies and practices developed by marketing since the 1990 ARF study and the USA Today Ad Meter system which, after all, have asked us to tell them what we like for decades.

Of course, the Facebook Like button does provide increased data about which ads are likable. With the Like Button, marketers can constantly experiment with variations on ads with test audiences, seeing what works and then scaling up small experiments quickly. With a universal measure provided by Like, marketers can test ads across different segments, greatly aiding the globalization of marketing campaigns.

But this only begins to describe the continual monitoring of users who have clicked Like in Facebook. The choice to like an ad or brand in Facebook is seen as an affirmative interaction with that brand – and an agreement to have one’s profile image associated with that brand and to have that approval follow you across the Web. If you like a brand, you must like to be a target for marketing messages, both from that brand and from others similar to it. You’re providing just a bit more information to help Facebook build a profile of your tastes and desires, all of which is for sale.

But again, these things are not really all that new. Since even before the advent of Liking Studies, marketers have experimented with advertising messages and tracked users to determine ad effectiveness. Whether the branding happens on TV, in a magazine, or online, we like, we buy. We like, they know. The science of marketing has always been the science of placing us in taxonomies based on what we like.

So what is new about Facebook and the Like button? Oddly enough, it reveals too much. The great sin of Facebook is that it made “like” far too important and too obvious. Marketing is in part the practice of eliding the underlying complexity, messiness, and wastefulness of capitalist production with neat abstractions. Every ad, every customer service interaction, every display, and every package contributes to the commodity fetish, covering up the conditions of production with desire and fantasy. As such, Facebook may reveal too much of the underlying architecture of emotional capitalism. The Like button tears aside this veil to reveal the cloying, pathetic, Willy Lomanesque need of marketers to have their brands be well-liked. Keep liking, keep buying. Like us! Like us! Like us!

Liking in marketing was always meant to be a metonym for many other complex processes — persuasion, affect, cognition, recall — but it wasn’t meant to be exposed to the public as such. In Facebook, however, the “Like” button further reduces this reduction and makes it visible, making the whole process somewhat cartoonish and tiresome. The consequences can be seen in “Like us on Facebook to enter to win!” promotions and the obsession with Like counts among businesses large and small (not to mention the would-be “personal branded“).

Because likability is now so visible, so prevalent as the preferred emotional response to brands and ideas, users have predictably called for the expansion of the emotional repertoire. They call for a Dislike button. At first glance, we might think this binary-emotional expansion would be welcome to marketers: it would add to their collected data on our desires. However, marketing’s sub-field of Liking Studies has already revealed that disliked ads poison everything they touch. Negative sentiment – disliking – is asymmetrical in its power to shape consumer’s opinions of a brand: for every 10 likes, 1 dislike could tear a brand apart. Such negative emotion requires much brand damage control. One thing Facebook will never do, then, is install a Dislike button.

This is not to say that Facebook won’t introduce other binary-emotional switches. Facebook’s flirtation with a Want button indicates their potential willingness to expand our binary-emotional repertoire. One could imagine users getting a Love button. But we are not allowed to dislike. And herein lies a way out of the Like Economy. Dissent, dissensus, refusal are not easily afforded in Facebook. Dissenters have to work for it: they have to write out comments, start up a blog, seek out other dislikers. They are not lulled into slackivism or “clickivism,” replacing the work of activism with clicking “like” on a cause as if the sheer aggregate of sentiment will make someone somewhere change something.

Instead, frustrated dislikers must think through their negative affect and find ways to articulate it into networks of dislike. If dislike scares off brands, so be it. Brands aren’t going to fix the world’s problems – but the dislikers might.

Love Thyself

To masturbate, whetherrealormetaphoristolove. To love, whetherrealormetaphoristomasturbate. How silly John.* My last lover is missed. Real or in metaphor. Not silly, John. She's just, well you know what I mean, "just" now. * As if playing with yourself could be love. Realormetaphorjust.

Tuesday, March 26, 2013

The Physics arXiv Blog

March 14, 2013

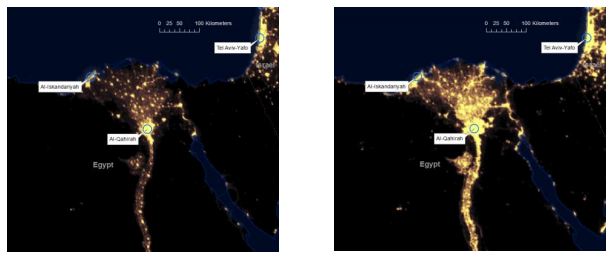

Global Night Light Patterns Reveal Economic Shift to the East

The mean centre of world lighting is moving east at the rate of 60

km per year, according to a new analysis of archived satellite images

The amount of light produced by a society is closely correlated with its economic status–rich developed countries tend to be brighter at night than poor developing ones. So an interesting question is how the distribution of light across our planet is changing over time.

Today we get an answer thanks to the work of Nicola Pestalozzi, Peter Cauwels and Didier Sornette at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. These guys have used data released by the US Defense Meteorological Satellite Program which has monitored night light levels around the planet continuously since the mid-1960s.

Various groups have studied this data to show how changes in night lights provide a useful way of monitoring things like population growth, energy consumption and gross domestic product, particularly in countries where official statistics are hard to come by.

These groups have significantly enhanced the data by processing in various ways such as removing the effects of fires, which burn brightly for short periods of time, and by combining the data for an entre year to produce an annual picture of light production.

Pestalozzi, Cauwels and Sornette look in particular at the dynamics of night lights. They calculate the planet’s mean centre of light and measure how it has moved in the last couple of decades. “Over the past 17 years, [the center of light] has been gradually shifting eastwards over a distance of roughly 1000 km, at a pace of about 60 km per year,” they say.

They’ve also used night lights as a way to monitor all kinds of other changes such as the expansion of developing countries like Brazil and India, the drop in light levels in countries suffering from demographic decline and a reduction in urban population like Russia and the Ukraine, and the success of light pollution abatement programs in countries such as Canada and the United Kingdom.

Perhaps their most fascinating insight is in the rapid increase of economic regions such as the Nile Delta (see above) and the area around Shanghai. Pestalozzi, Cauwels and Sornette say that the data clearly shows how light produced by these areas in the developed world has remained remarkably stable, with the New York metropolitan region easily topping the rankings by sheer size.

However, the amount of light produced by these areas in the developing world has increased dramatically with Shenzen in China and the Nile Delta in north Africa showing the biggest increases.

An interesting exception is the region around Milan in Italy which has dramatically increased light production because of agglomeration with the surrounding areas of Monza, Bergamo and Brescia.

Of course, night light dynamics will never replace traditional measures of economic activity but it does provide a global view that is easy to measure and interpret. Interesting stuff!

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1303.2901: Dynamics and Spatial Distribution of Global Nighttime Lights

8 Tips for Growing A Greenhouse Organic Vegetable Garden

8 Tips for Growing A Greenhouse Organic Vegetable Garden

| Written by Jean Gallagher |

There are many advantages to growing organic vegetables in a greenhouse. Although you won't automatically be weed and pest free just because you are growing indoors, you will have complete control over how you protect your precious organic plants. Lean to greenhouses are especially well adapted to an organic garden as you can place them close to your kitchen door. Because lean-tos are attached to a structure, there are only three glazed sides. This makes them energy efficient because warm and cool temperatures can be diverted from your home through the common wall your home shares with the attached lean to. Here are eight tips for producing healthy and delicious organic fruits and vegetables for your kitchen garden. 1. Avoid greenhouses made from synthetic materials. Many side panels are now made from various types of plastics and polycarbonates, but true organic aficionados opt for glass greenhouses. The panel is even more important than the frame because moisture will collect on the panel's surface and drip on your garden.  2. Plan your vegetable garden layout in advance. Using graph paper, plot where you will place each plant in your greenhouse. Although "companion planting" is not a new concept, the use of it in an organic greenhouse cannot be over emphasized. Greenhouse gardening has its own share of pest problems, many which can be avoided naturally by the use of companion planting.

3. Start with organic soil. Don't skimp on the quality of the soil or

the organic additives you'll add to your soil like compost, manure or

sea products like kelp. Additives are like fertilizer, they boost the

health of your soil. Remember, additives vary depending on what plants

you grow. Different plants have different needs.

3. Start with organic soil. Don't skimp on the quality of the soil or

the organic additives you'll add to your soil like compost, manure or

sea products like kelp. Additives are like fertilizer, they boost the

health of your soil. Remember, additives vary depending on what plants

you grow. Different plants have different needs.Be careful. If you plant taller vegetables and fruits such as tomatoes or corn directly into the ground make sure they have plenty of ceiling space to grow to their full height. Also you must be certain that the soil is free from dangerous organisms and toxins. If you suspect your soil contains toxins, purchase a soil test kit from your seed supplier. Another option is to sterilize your soil. Put your desired amount of soil in an oven roasting bag, add enough water to dampen the soil and tie it shut. Poke a meat thermometer through the bag and heat in a 200 degree oven. Keep the temperature of the soil as close to 170 degrees as possible for 30 minutes. The temperature of the soil won't reach the temperature of the oven within 30 minutes, but it's best to keep an eye on the thermometer. If it gets too warm simply turn the oven down, or even off if you are nearing the end of the 30 minutes cycle. Put the cooled sterilized soil into pots and sink them directly into the ground. 4. Compost. This is the most important and most affordable factor in your vegetable garden. Remember to keep your compost organic. That means everything you toss in there has to be organic. If you put anything that contains chemicals into your compost bin, your compost will contain chemicals.  5. Control weeds before they grow. Lay a 1" to 2" thickness of newspaper on top of the soil and cover with about the same amount of soil or mulch. It's not an exact science. The thicker the paper, the more it will deter the weeds. Most newspaper inks are soy-based so your little plants will stay happy and healthy. Do not use the glossy color inserts as they are not only very toxic, water cannot penetrate the glossy surface. Plain old newspaper however, will work wonders. It will also decompose over time and be a healthy additive to your soil. 6. Know your natural herbicides. If an extreme bug infestation hits and you find you need an herbicide, a tried and true method is the use of an organic soap mixture. Buy the cheapest type of lemon dish soap you can find. The cheap brands will usually not have a lot of the toxic additives that the more costly labels use. Mix one tablespoon of the soap into a gallon of water and pour into a sprayer. Apply liberally on top and bottom of the leaves. Re-apply every one or two weeks. The soap mixture has the added benefit of reducing the risk of various diseases that can develop. 7. Pull spent plants from the soil. After you harvest your fruits and vegetables, pull them from the soil and toss them in your compost bin for next year's garden. Removing spent plants from the soil helps maintain the nutrients in the soil and discourage pests. 8. Buy a cookbook! Get yourself a good organic fruit and vegetable cookbook and enjoy your harvest! Image Credits: tomatoes: qmnonic, carrots: John-Morgan, marigolds: Swami Stream, lavender: Swami Stream |

Damn

Voyager 1 has entered a new region of space, sudden changes in cosmic rays indicate

20 March 2013

AGU Release No. 13-11

For Immediate Release

WASHINGTON – Thirty-five years after its launch, Voyager 1 appears to

have travelled beyond the influence of the Sun and exited the

heliosphere, according to a new study appearing online today.AGU Release No. 13-11

For Immediate Release

The heliosphere is a region of space dominated by the Sun and its wind of energetic particles, and which is thought to be enclosed, bubble-like, in the surrounding interstellar medium of gas and dust that pervades the Milky Way galaxy.

On August 25, 2012, NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft measured drastic changes in radiation levels, more than 11 billion miles from the Sun. Anomalous cosmic rays, which are cosmic rays trapped in the outer heliosphere, all but vanished, dropping to less than 1 percent of previous amounts. At the same time, galactic cosmic rays – cosmic radiation from outside of the solar system – spiked to levels not seen since Voyager's launch, with intensities as much as twice previous levels.

The findings have been accepted for publication in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

"Within just a few days, the heliospheric intensity of trapped radiation decreased, and the cosmic ray intensity went up as you would expect if it exited the heliosphere," said Bill Webber, professor emeritus of astronomy at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces. He calls this transition boundary the "heliocliff."

In the GRL article, the authors state: "It appears that [Voyager 1] has exited the main solar modulation region, revealing [hydrogen] and [helium] spectra characteristic of those to be expected in the local interstellar medium."

However, Webber notes, scientists are continuing to debate whether Voyager 1 has reached interstellar space or entered a separate, undefined region beyond the solar system.

"It's outside the normal heliosphere, I would say that," Webber said. "We're in a new region. And everything we're measuring is different and exciting."

The work was funded by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

Monday, March 25, 2013

Sunday, March 24, 2013

Such utter bullshit...academia wins

Outside the Citadel, Social Practice Art Is Intended to Nurture

Regina Martinez for The Pulitzer Foundation for the Arts

A town-hall meeting on racial and economic issues at the Pulitzer Foundation for the Arts in St. Louis.

By RANDY KENNEDY

Published: March 20, 2013

In Detroit a contemporary-art museum is completing a monument to an

influential artist that will not feature his work but will instead

provide food, haircuts, education programs and other social services to

the general public.

Enlarge This Image

Hassan Ali Noor/Creative Time Reports

Marisa Mazria Katz interviews a musician in Nairobi,

Kenya, for Creative Time Reports, run by a New York nonprofit.

Corine Vermuelen

A re-creation of the childhood home of the artist

Mike Kelley that will be a social-services site at the Museum of

Contemporary Art Detroit.

Peter Walsh

Portraits sketched round-robin at a school where classes were paid for through bartering.

In New York an art organization that commissions public installations

has been dispatching a journalist to politically precarious places

around the world where she enlists artists and activists — often one and

the same — to write for a Web site

that can read more like a policy journal than an art portal. And in St.

Louis an art institution known primarily for its monumental Richard

Serra sculpture is turning itself into a hub of social activism,

recently organizing a town-hall meeting where 350 people crowded in to talk about de facto segregation, one of the city’s most intractable problems.

If none of these projects sound much like art — or the art you are used

to seeing in museums — that is precisely the point. As the commercial

art world in America rides a boom unlike any it has ever experienced,

another kind of art world growing rapidly in its shadows is beginning to

assert itself. And art institutions around the country are grappling

with how to bring it within museum walls and make the case that it can

be appreciated along with paintings, sculpture and other more tangible

works.

Known primarily as social practice, its practitioners freely blur the

lines among object making, performance, political activism, community

organizing, environmentalism and investigative journalism, creating a

deeply participatory art that often flourishes outside the gallery and

museum system. And in so doing, they push an old question — “Why is it

art?” — as close to the breaking point as contemporary art ever has.

Leading museums have largely ignored it. But many smaller art

institutions see it as a new frontier for a movement whose roots stretch

back to the 1960s but has picked up fervor through Occupy Wall Street

and the rise of social activism among young artists.

“Say what you will, this stuff is happening, and you might want to put

your head in the sand and say, ‘I wish it was 40 years ago and it was

different and art was more straightforward,’ but it’s not,” said Nato Thompson, the chief curator of Creative Time,

a New York nonprofit that is known mostly for temporary public art

installations but has been delving deeply into the movement.

Works can be as wildly varied as a community development project in Houston that provides both artists’ studios and low-income housing, summer camps and workshops for teenagers run by an artist collective near Los Angeles or a program in San Francisco founded by artists and financed by the city that helps turn yards, vacant lots and rooftops into organic gardens.

Art of this kind has thrived for decades outside the United States,

mostly in Europe and South America, but has recently caught fire with a

new generation of American artists in what is partly a reaction to the

art market’s distorting power, fueled by a concentration of

international wealth. Many artists, however, say the motivation is much

broader: to make a difference in the world that is more than aesthetic.

“The boundary lines about how art is being made are becoming much

blurrier,” said Laura Raicovich, who was hired last year by Creative

Time as its director of global initiatives and to run a Web site called Creative Time Reports.

The site’s recent pieces include a video by an Egyptian-Lebanese artist about Tahrir Square, the locus of the Egyptian uprising two years ago, and a short film

about family debt in America made by a self-described “debt resistance”

art collective with roots in the Occupy Wall Street movement.

“We’re not trying to do what journalism does,” Ms. Raicovich said. “But

we think artists can supplement and complement it through a different

lens. And what they’re doing is art.”

Social-practice programs are popping up in academia and seem to thrive

in the interdisciplinary world of the campus. (The first dedicated

master of fine arts program in the field was founded in 2005 at the California College of the Arts

in San Francisco, and today there are more than half a dozen.) But for

art institutions the problems are trickier: How can you present art that

is rarely conceived with a museum or exhibition in mind, for example

community projects, often run by collaboratives, that might go on for

years, inviting participation more than traditional art appreciation?

At the Pulitzer Foundation for the Arts,

a private institution founded by the collector and philanthropist Emily

Rauh Pulitzer that opened in St. Louis in 2001, the staff for many

years included two full-time social workers who helped former prison

inmates and homeless veterans as part of the curatorial program. And in

December the foundation, responding to a 2012 BBC report about racial and economic disparities in St. Louis, held a town-hall meeting

on the issue. The goal was to open a dialogue with people who live near

the institution, which sits near a stark north-south divide between

mostly white and African-American neighborhoods.

“We hoped maybe 100 people would show up, and more than 350 did,” said

Kristina Van Dyke, the foundation’s director, who collaborated with the Missouri History Museum

in organizing the event. As the foundation approached its 10th

anniversary, she said, “we wanted to start envisioning art more broadly,

as a place where ideas can happen and action might be able to take

place.”

“The question became: Could we effect social change through art, plain

and simple?” she said, adding that the foundation is now exploring ways

to orient its programming toward design projects that would help the

poor, for example. “To me art is elastic. It can respond to many

different demands made on it. At the same time I have to say that I

don’t believe all institutions have to do these kinds of things, or

should.”

Some in the art world feel that all institutions (and artists) should

resist the urge completely. Maureen Mullarkey, a New York painter, wrote

on her blog, Studio Matters,

that such work only confirmed her belief “that art is increasingly not

about art at all.” Instead, she argued, it is “fast becoming a variant

of community organizing by soi-disant promoters of their own notions of

the common good.”

But many institutions, especially those in cities and neighborhoods with

pressing social problems, see the need to extend their reach.

The Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, for example, is constructing a final work by the artist Mike Kelley, who committed suicide

last year, that will function as a kind of perpetual social-practice

experiment. Although Kelley was never identified with the movement, he

specified before his death that the work, “Mobile Homestead”

— a faithful re-creation of his childhood ranch-style home that will

sit in a once-vacant lot behind the museum — should not be an art

location in any traditional sense but a small social-services site, with

possible additional roles as space for music and the museum’s education

programs. Whether visitors will understand that the house is a work of

art and a continuing performance is an open question. Smaller

institutions like the Hammer Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and the Queens Museum of Art, which is acknowledged as a pioneer of social-practice programming, have also begun bringing the movement into the spotlight. (Tania Bruguera,

a New York artist who is known for helping immigrants and has been

supported by the Queens Museum and Creative Time, sometimes explains

social-practice art with an anti-Modernist call to arms: “It’s time to

restore Marcel Duchamp’s urinal to the bathroom.”)

Still, the political nature of the movement propels it into territory

that is unfamiliar to many artists and art institutions. Last year, for

example, a group of artists boycotted a summit meeting that has been

held annually by Creative Time since 2009, saying they objected to the

participation of a digital art center supported by the Israeli

government. (Creative Time later made clear that the meeting received no

funds from the organization or the Israeli government.)

Mr. Thompson of Creative Time said that many of the most dedicated

social-practice artists see a huge divide between themselves and the

commercial art world. “There are artists who don’t want to be the

entertainment,” he said. “During a crisis of vast inequity they don’t

want to be the sideshow, off to the side juggling.”

Caroline Woolard, a 29-year-old Brooklyn artist whose projects include collaborating on temporary “trade schools”

where classes are paid for through bartering, said she became a

social-practice artist not because she objected to the commercial or

institutional art sectors but because she felt that the art world was

too isolated.

“It was the realization that the types of people who went to cultural

institutions — museums or galleries — were such a small section of any

possible public for the kind of work I was interested in,” she said. She

added, though, that she believed the movement would only broaden, and

that museums and even the commercial art world would have to find a way

to get involved.

“I do think that there will be ways for new kinds of collectors to

emerge who will support these kinds of long-term projects as works of

art,” said Ms. Woolard, who was recently asked by the Museum of Modern

Art’s education department to take part in a social-practice program, “Artists as Houseguests: Artists Experiment at MoMA,” over the next few months.

Pablo Helguera, who is organizing the experiment as the director of

adult and academic programs in MoMA’s education department, said that

departments like his, as opposed to curatorial ones, are often the doors

through which social-practice artists enter the museum world.

“There have always been artists working this way, but we started seeing

more and more of them,” Mr. Helguera said. “My theory is that the shift

began happening sometime after 9/11. I think it was the question ‘What

is the meaning of making art in the world like it is today?’ ”

Mr. Helguera, who has written a book

on the subject, “Education for Socially Engaged Art,” added that

galleries and museums are only now beginning to scope out the movement’s

contours. “The art world has these expectations,” he said. “It’s like

you’re supposed to deliver your fall collection and your spring

collection, and then what are you doing for the summer, for the art

fairs and the biennials?”

“But this kind of work doesn’t operate according to that calendar,” he

said. “It might mean a connection with some community or group of people

for years, maybe some artist’s whole life. It’s hard to bring to the

public. Sometimes it’s hard to define.”

Even those who live in the world of socially engaged art sometimes need help defining it. Justin Langlois, a Canadian artist, recently wrote

a wry David-Letterman-style list of questions that artists can pose to

themselves to determine whether they are indeed practicing social

practice. Question No. 19 was “Can your work be critiqued by a painter?”

Question No. 22: “If your project was a math equation, did the sum

always end up as a critique of capitalism?” And the final question:

“Were you asked to explain the reason you think your project is art?”

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)