HOME /

The Mouse Trap :

How one rodent rules the lab.

The Mouse Trap

The dangers of using one lab animal to study every disease.

Daniel Engber’s three-part series “The Mouse Trap: How One Rodent Rules the Lab” (published in Slate last November) has won the 2012 Communication Award

for the online category. The award is conferred annually by the

National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, and

Institute of Medicine with funding from the W.H. Keck Foundation to

honor “excellence in reporting and communicating science, engineering

and medicine to the general public.” Engber's exploration of the risks

of relying on mice for so much of our research brought an underreported

scientific problem to light for lay readers. You can revisit the series

below. undefined

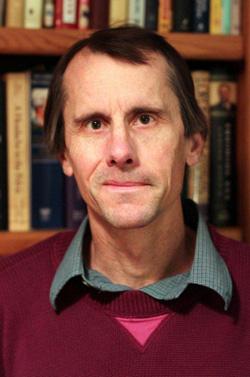

Mark Mattson knows a lot about mice and rats. He's fed them;

he's bred them; he's cut their heads open with a scalpel. Over a

brilliant 25-year career in neuroscience—one that's made him a

Laboratory Chief at the National Institute on Aging, a professor of

neuroscience at Johns Hopkins, a consultant to Alzheimer's nonprofits,

and a leading scholar of degenerative brain conditions—Mattson has

completed more than 500 original, peer-reviewed studies, using something

on the order of 20,000 laboratory rodents. He's investigated the

progression and prevention of age-related diseases in rats and mice of

every kind: black ones and brown ones; agoutis and albinos; juveniles

and adults; males and females. Still, he never quite noticed how fat they

were—how bloated and sedentary and sickly—until a Tuesday afternoon in

February 2007. That's the day it occurred to him, while giving a lecture

at Emory University in Atlanta, that his animals were nothing less (and

nothing more) than lazy little butterballs. His animals and everyone

else's, too.

Mattson was lecturing on a research program that he'd been conducting

since 1995, on whether a strict diet can help ward off brain damage and

disease. He'd generated some dramatic data to back up the theory: If

you put a rat on a limited feeding schedule—depriving it of food every

other day—and then blocked off one of its cerebral arteries to induce a stroke,

its brain damage would be greatly reduced. The same held for mice that

had been engineered to develop something like Parkinson's disease: Take

away their food, and their brains stayed healthier.

How would these findings apply to humans, asked someone in the

audience. Should people skip meals, too? At 5-foot-7 and 125 pounds,

Mattson looks like a meal-skipper, and he is one. Instead of having

breakfast or lunch, he takes all his food over a period of a few hours

each evening—a bowl of steamed cabbage, a bit of salmon, maybe some yogurt.

It's not unlike the regime that appears to protect his lab animals from

cancer, stroke, and neurodegenerative disease. "Why do we eat three

meals a day?" he asks me over the phone, not waiting for an answer.

"From my research, it's more like a social thing than something with a

basis in our biology."

Illustration by Rob Donnelly.

But Mattson wasn't so quick to prescribe his stern feeding schedule

to the crowd in Atlanta. He had faith in his research on diet and the

brain but was beginning to realize that it suffered from a major

complication. It might well be the case that a mouse can be starved into

good health—that a deprived and skinny brain is more robust than one

that's well-fed. But there was another way to look at the data. Maybe

it's not that limiting a mouse's food intake makes it healthy, he

thought; it could be that not limiting a mouse's food makes it

sick. Mattson's control animals—the rodents that were supposed to yield a

normal response to stroke and Parkinson's—might have been overweight,

and that would mean his baseline data were skewed.

"I began to realize that the ‘control’ animals used for research

studies throughout the world are couch potatoes," he tells me. It's been

shown that mice living under standard laboratory conditions eat more

and grow bigger than their country cousins. At the National Institute on

Aging, as at every major research center, the animals are grouped in

plastic cages the size of large shoeboxes, topped with a wire lid and a

food hopper that's never empty of pellets. This form of husbandry, known

as ad libitum feeding, is cheap and convenient since animal

technicians need only check the hoppers from time to time to make sure

they haven’t run dry. Without toys or exercise wheels to distract them,

the mice are left with nothing to do but eat and sleep—and then eat some

more.

That such a lifestyle would make rodents unhealthy, and thus of

limited use for research, may seem obvious, but the problem appears to

be so flagrant and widespread that few scientists bother to consider it.

Ad libitum feeding and lack of exercise are industry-standard

for the massive rodent-breeding factories that ship out millions of lab

mice and rats every year and fuel a $1.1-billion global business in

living reagents for medical research. When Mattson made that point in

Atlanta, and suggested that the control animals used in labs were

sedentary and overweight as a rule, several in the audience gasped. His

implication was clear: The basic tool of biomedicine—and its workhorse

in the production of new drugs and other treatments—had been transformed

into a shoddy, industrial product. Researchers in the United States and

abroad were drawing the bulk of their conclusions about the nature of

human disease—and about Nature itself—from an organism that's as

divorced from its natural state as feedlot cattle or oven-stuffer

chickens.

Mark Mattson, National Institute on AgingCourtesy of the National Institute on Aging.

Mattson isn't much of a doomsayer in conversation. "I realized that

this information should be communicated more widely," he says without

inflection, of that tumultuous afternoon in Atlanta. In 2010, he

co-authored a more extensive, but still measured, analysis of the

problem for the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The paper, titled " 'Control' laboratory rodents are metabolically morbid: Why it matters," laid out the case for how a rodent obesity epidemic might be affecting human health.

Standard lab rats and lab mice are insulin-resistant, hypertensive,

and short-lived, he and his co-authors explained. Having unlimited

access to food makes the animals prone to cancer, type-2 diabetes, and

renal failure; it alters their gene expression in substantial ways; and

it leads to cognitive decline. And there's reason to believe that ragged

and rundown rodents will respond differently—abnormally, even—to

experimental drugs.

Mattson has seen this problem in his own field of research. Twenty

years ago, scientists started to develop some new ways to prevent brain

damage after a stroke. A neurotransmitter called glutamate had been

identified as a toxin for affected nerve cells, and a number of drug

companies started working on ways to block its effects. The new

medicines were tested in rats and mice with great success—but what

worked in rodents failed in people. After a series of time-consuming and

expensive clinical trials, the glutamate-blockers were declared a bust:

They offered no benefit to human stroke patients.

Now Mattson has an idea for why the drugs didn't pan out: All the

original test-animals were chubby. If there's something about the brain

of an obese, sedentary rodent that amplifies the effects of a

glutamate-blocker, that would explain why the drugs worked for a

population of lab animals but not in the more diverse set of human

patients. This past June, he published a paper

confirming the hunch: When he put his test mice on a diet before

administering the glutamate-blockers, the drugs' magical effects all but

disappeared.

Many promising treatments could be failing for the same reason,

Mattson argues, and other trials should be re-examined—but that's

unlikely to happen anytime soon. "It comes down to money and resources,"

he says. "There's some fraction of studies that may have been

compromised by [these] issues, but there's no way to know unless one

does the experiment with the proper controls."

That's the drawback of the modern lab mouse. It's cheap, efficient,

and highly standardized—all of which qualities have made it the favorite

tool of large-scale biomedical research. But as Mattson points out,

there's a danger to taking so much of our knowledge straight from the

animal assembly line. The inbred, factory-farmed rodents in use

today—raised by the millions in germ-free barrier rooms, overfed and

understimulated and in some cases pumped through with antibiotics—may be

placing unseen constraints on what we know and learn.

"This is important for scientists," says Mattson, "but they don't think about it at all."

* * *

Mattson is not the only one with doubts, nibbling away at the corner

of his cage. The rise of the factory mouse has implications that extend

far beyond his work on Parkinson's disease and stroke. By focusing so

intently on one organism, raised in a certain way, we may be limiting

our knowledge of cancer, too, and heart disease, and tuberculosis—the

causes of death for many millions of people

every year. If Mattson is right, science may be faced with a problem

that is mind-boggling in its scope. Funding agencies in the United

States and Europe will spend hundreds of millions of dollars in the

coming years to further fiddle with and refine the standard organism,

doubling down on a bet that goes back at least six decades: Establishing

a single animal as the central determinant of how we study human

illness, design new medicines, and learn about ourselves.

Just how ubiquitous is the experimental rodent? In the hierarchy of

lab animal species, the rat and mouse rule as queen and king. A recent

report from the European Union counted up the vertebrates used for

experiments in 2008—that's every fish, bird, reptile, amphibian, and

mammal that perished in a research setting, pretty much any animal more

elaborate than a worm or fly—and found that fish and birds made up 15

percent; guinea pigs, rabbits, and hamsters contributed 5 percent; and

horses, monkeys, pigs, and dogs added less than 1 percent. Taken

together, lab rats and lab mice accounted for nearly all the

rest—four-fifths of the 12 million animals used in total. If you extend

those proportions around the world, the use of rodents is astonishing:

Scientists are going through some 88 million rats and mice for their

experiments and testing every year.

Dead mice pile up more than three times faster than dead rats, which

makes sense given their relative size. Cheap, small animals tend to be

killed in greater volumes than big ones. A researcher might run through

several dozen mice, half a dozen rabbits, or a pair of monkeys to

achieve the same result: one published paper. More striking, then, is

the extent to which papers about rats and mice—however many animals go

into each—dominate the academic literature. According to a recent survey

of animal-use trends in neuroscience, almost half the journal pages published between 2000 and 2004 described experiments conducted on rats and mice.

A survey of the National Library of Medicine's database of more than 20 million academic citations

shows the same trend across the whole of biomedicine. Since 1965, the

number of published papers about dogs or cats has remained fairly

constant. The same holds true for studies of guinea pigs and rabbits.

But over that 44-year stretch, the number of papers involving mice and

rats has more than quadrupled. What about the simpler organisms that researchers tend to poke and prod—yeast and zebra fish and fruit flies and roundworms?* By 2009, the mouse itself was responsible for three times as many papers as all of those combined.

That is to say, we've arrived at something like a monoculture in

biomedicine. The great majority of how we understand disease, and

attempt to cure it, derives from a couple of rodents, selected—for

reasons that can seem somewhat arbitrary in retrospect—from all the

thousands of other mammals, tens of thousands of other vertebrates, and millions of other animal species

known to walk or swim or slither the Earth. We've taken the mouse and

the rat out of their more natural habitats, from fields and barns and

sewers, and refashioned them into the ultimate proxy for ourselves—a

creature tailored to, and tailored by, the university basement and the

corporate research park.

It's just the latest step in a trend that began more than a century

ago. The splendid menagerie that once formed the basis for physiological

study—the sheep, the raccoons, the pigeons, the frogs, the birds, the

horses—has since the early 1900s been whittled down to a handful of key "model systems":

Animals that are special for not being special, that happen to flourish

under human care and whose genes we can manipulate most easily; the

select and selected group that are supposed to stand in for all

creation. Where scientists once tried to assemble knowledge from the

splinters of nature, now they erect it from a few standardized parts: An

assortment of mammals, some nematodes and fruit flies, E. coli bacteria and Saccharomyces

yeast. Even this tiny toolkit of living things has in recent decades

been shrunk down to a favored pair, the rat and mouse. The latter in

particular has become a biological Swiss army knife—a handyman organism

that can fix up data on cancer, diabetes, depression, post-traumatic

stress, or any other disease, disorder, or inconvenience that could ever

afflict a human being. The modern lab mouse is one of the most glorious

products of industrial biomedicine. Yet this powerful tool might have

reached the limit of its utility. What if it's taught us all it can?

* * *

The government's top researcher

on tuberculosis—still one of the world's most deadly infections—seems

to be running a midsized wildlife park out of his Maryland home. In a

modest house on a tree-lined street in Germantown, Clif Barry keeps two

kinds of turtles, three veiled chameleons, two Jackson's chameleons, six

species of frogs, half a dozen fish tanks (filled with cichlids,

goldfish, and piranhas, kept separately), two dogs (named Jacques and

Gillian), and an Australian tree python. "I'm an animal person," he

tells me. "My house would require a zookeeper's license if Montgomery

County knew what I had."

Clifton E. Barry, 3rd, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious DiseasesCourtesy of Clifton E. Barry, 3rd.

Twenty miles away in Bethesda, though, where Barry serves as chief of

the Tuberculosis Research Section at the National Institute of Allergy

and Infectious Diseases, a single animal has taken over the ecosystem.

It has infested every paper and conference, and formed a living,

writhing barrier to new drugs on their way to clinical trials. "We've

always only tested things in mice," Barry tells me by phone one

afternoon. "The truth is that for some questions, mice give you a very

nice and easy model system for understanding what's happening in humans,

but mice are mice, and people are people. If we look to the mouse to

model every aspect of the disease for man, and to model cures, we're

just wasting our time."

The problem, he says, begins with the three M’s. The process of drug

discovery has been carried out in the same way for decades. You start by

testing a new compound in a Petri dish, to find out whether it can slow

the growth of a particular bacterium in culture. That gives you the

smallest dose that has an effect, known as the minimum inhibitory

concentration, or "MIC"—the first M. Then you move to a living animal:

Does the compound have any effect on the course of disease in a lab

mouse? If so, you've cleared the second M, and you're ready to test the

compound in the third M, man. Each step leads to the next: No drug can

be tested in man until it's been shown to work in mice, and no drug is

tested in mice until it's been shown to have a reasonable effect in the

dish. "The bad part of that," says Barry, "is that no part of it is

predictive:" A new compound that succeeds in the dish might flunk out in

the mouse, and something that can cure tuberculosis in a mouse could

wash out in people.

Take the example of pyrazinamide, one of the front-line drugs in the

treatment of tuberculosis. Along with three other antibiotics, it forms

the cocktail that remains, despite ongoing research, our only way of

defeating the infection. But pyrazinamide didn't make it through the

three Ms: It does nothing in the dish—there's no MIC whatsoever—and it

has a weak effect in mice. According to Barry, if a compound like that

were discovered in 2011, it would never make its way into clinical

trials. Forty years ago, the system wasn't so rigid. A prominent

physician and researcher at Britain's Medical Research Council named Wallace Fox

saw something intriguing in the animal data: Pyrazinamide's action

seemed to persist when those of other drugs had stopped. He insisted on

testing the drug in humans, and its effects were profound. The fact that

nothing gets to humans today without first passing the mouse test, says

Barry, "has cost us a new generation of medicines."

Indeed, there's been no real breakthrough in treating tuberculosis—no

major pharmaceutical discoveries—since the early 1970s. The first

antibiotic to have any success against the tuberculosis mycobacterium,

the first that could penetrate its waxy coating, was discovered (and

tested in guinea pigs) in the early 1940s. The best vaccine we have was

first used in humans in 1921. (It works pretty well against severe

childhood forms of the disease, but less so otherwise.) And the closest

thing we have to a miracle cure—the multidrug cocktail that doesn’t work

against every strain and requires a six-month course of treatment with

severe side effects—was finalized during the Nixon administration. Since

then, almost every new idea for how to treat TB has come from

experiments on lab mice. These have given us enough new data to drown

the infected in a tsunami of graphs and tables, to bury them in animal

carcasses. Yet we've made little progress—OK, no progress at all—in

treating the human disease. Tuberculosis causes more than 2 million

deaths every year, and we're using the same medicines we had in 1972.

One major problem with the mouse model—and the source of its spotty

track record in the clinic—is well-known among those in the field: The

form of TB that mice happen to get isn't all that much like our own. A

human case of the disease begins when infectious bacilli are inhaled

into the lungs, where they grow in number as the immune system sends in

its soldiers to fight them off. White blood cells swarm the bacteria in a

rolling, alveolar scrum, forming a set of pearly-white masses the size

of golf balls called granulomas. These are where the war between body and invader plays out in a series of contained skirmishes.

As more immune cells are recruited to fight off the infection, some

of the balls swell and stratify into a more developed form: A sphere of macrophages and lymphocytes

packed inside a fibrous shell, with a cottage cheese clump of dead

cells and bacteria at its core. At this point the battle reaches a

stalemate: The bacteria stop dividing; the body has controlled, but not

eliminated, the infection. For most people who have the disease, it's a

ceasefire that holds indefinitely.

But for some patients a latent case of tuberculosis can suddenly

become active. The granulomas rupture and propagate, spilling thousands

of organisms into the lungs, where they can be aerosolized, coughed up,

and passed on to a new host. Left untreated, the infection migrates into

the bloodstream and other organs; widespread inflammation leads to

burst arteries or a ruptured esophagus; and in about half of all cases,

the patient dies.

The layered granuloma is the defining feature of human tuberculosis:

The place where the host fights the infection (successfully or not), and

the necessary site of action for any drug. To cure the disease, a

treatment must be able to penetrate each ball of cells, whatever its

type or composition; every last bacterium must be destroyed. "It's the

structure of those granulomas that makes it so difficult to treat TB,"

says Barry. And they simply don't exist in mice.

If you infect a mouse with TB—if you spritz a puff of infected air into its nostrils through a trumpet,

as so many labs do around the world—the animal's lungs quickly fill up

with bacteria and immune cells, like a nasty case of pneumonia. There

are no discrete balls of tissue, no well-defined granulomas sheathed in

fibrin, no array of structures that harbor the bugs at various stages of

development. The mice have no special, latent form of TB, either, and

no way to pass on the disease. They simply die, after a year or two, of a

slow and progressive decline.

That's why we've made so little progress using mice to generate new

drugs and treatments, Barry tells me. In the absence of a clear,

granulomatous response upon which to model human disease, the second M

has become a massive roadblock in the path to a cure. "The vast majority

of the money that we spend in clinical trials based on mouse data is

completely wasted," he says.

* * *

If you ask Clif Barry why we're still using the mouse to study

tuberculosis, or Mark Mattson why we continue to test new drugs on obese

and sedentary rodents, they'll tell you the same thing: Because that's

what we've always done—we're in a rut. But to an outsider—say, a

journalist who's trying to understand the place of the mouse in the

broad enterprise of biomedicine—that explanation doesn't make sense. If

you think of science as an industry of ideas, or a marketplace for

medical technology, then there ought to be a clear and guiding incentive

for greater efficiency in the lab—an invisible hand of self-interest

with its fingers curled around every pipette and microtome. Any firm

that finds a miracle drug can earn hundreds of millions

in an IPO; any university professor who makes a breakthrough will gain

fame and tenure; any disease that's cured may save countless lives. With

so much on the line, how is it possible that all interested parties

would be hamstrung by the same faulty method? Through what success or

subterfuge did one particular rodent species earn its exalted spot among

the three M’s of drug discovery? (Why should the second M stand for mouse, instead of monkey, marsupial, or mollusk?) In short: What's so wonderful about the lab mouse?

There's a standard answer to that question, one that can be repeated

almost verbatim by biologists from across the spectrum of medical

fields. The mouse is small, it's cheap, it's docile, and it's amenable

to the most advanced tools of genetic engineering.

It's true that rats and mice are smaller, cheaper, and

faster-breeding than many other mammals. Our last common ancestor lived

80 million years ago, which makes them closer cousins to us, in

evolutionary terms, than either cats or dogs. (We share about 95 percent

of our genome—although such comparisons tend to be more rhetorical than

scientific.) And even among those who worry over the welfare of

laboratory animals, there isn't much indignation at their use. (Rats and mice are denied

many of the rights afforded other experimental mammals.) But a similar

dossier could have been assembled in favor of any of a number of small

creatures, some of which might be better-suited to answer certain

questions. If you want to know about the visual system, for example, why

use an animal that sniffs and whisks its way through the world? How

about one that depends on its eyes, like a squirrel?

A rational calculation of its benefits and drawbacks misses the point

of the modern lab animal. The real source of its influence, and the

origin of its unique appeal to scientists around the world, is the

simple fact of its having been chosen at all. Once we decided to focus

our efforts on the rat and mouse, we learned how to fine-tune those

species to fit our every need. When new technologies and methods entered

the lab—improved products for animal care, better reagents for

biochemistry, novel means for genetic manipulation—we tested them on,

and tailored them to, our standard rodents. Meanwhile, the more rat and

mouse data that accrued in scientific journals, the more tempting it was

to devise follow-up experiments using the rat and mouse once more. In

that sense, Barry and Mattson are right: We use these animals because

that's what we've always done.

Mouse receives a drop of fluid from a syringe, U.S. Center for Biologics Evaluation and ResearchPhotograph by Jerry Hecht, image from the National Library of Medicine.

The feedback loop began more than 60 years ago, when federal

investment in biomedicine was growing at an exponential rate. To

eradicate the last vestiges of infectious disease, win the war on

cancer, and otherwise mobilize the nation's resources for an industrial

revolution in science, the government needed a more streamlined research

model—a lab animal, or a set of lab animals, that could be standardized

and mass-produced in centralized facilities, and distributed across the

country for use in all kinds of experiments. An efficient use of

federal research funds demanded an efficient organism for research.

In part because of their size and breeding capacity, and in part

because they'd been used in laboratories since the turn of the century,

the rat and mouse were selected for this role. As major research grants

began to flow from Washington in the 1950s and 1960s, private rodent

breeders picked up huge contracts with government-funded labs. Animal

factories expanded rapidly throughout the Northeast, and then around the

world. Lab mice were shipped out to the front lines of industrial

medicine for cancer-drug screenings, radiation exposure tests, and even

routine medical procedures. (Some early pregnancy tests

required the injection of urine into female mice.) Rats, meanwhile,

were the favored test-animals for industrial toxicology, and the norm in

studies of behavioral psychology. Supply and demand surged upward in a

spiral of easy breeding and cheap slaughter.

Standardized cages, food pellets, and husbandry techniques lowered

costs. (A basic lab mouse now runs about $5 and can be maintained for a

nickel a day.) Standardized suppliers made research more convenient. (A

scientist can order animals for second-day delivery online, or by

calling 1-800-LAB-RATS.) And standardized breeds—which ensure that every

mouse or rat is a virtual clone of both its siblings and its

ancestors—made it easier to replicate and verify studies from one lab to

another.

This process reached its apotheosis 30 years ago, when decades of

investment in the rodent model paid off with an extraordinary invention:

The transgenic mouse. In December 1980, a group at Yale announced that

it had injected a bit of foreign DNA

into a fertilized mouse egg, and then implanted the embryo to produce a

transformed but healthy offspring. Now the mammalian genome could be

modified at will.

One discovery came after another: In '81, researchers at Cambridge managed to grow a population of embryonic stem cells

for the very first time—again derived from the standard lab mouse. By

the end of the decade, these had made possible an even more powerful

research tool, the "gene knockout" mouse. Now we could design living

animals with precise twists or snips in the curls of their DNA.

Individual genes could be mutated, deleted, or added de novo,

and a golden age of mouse research soon followed. Over the next 20

years—and running up through the present day—lab animals were engineered

such that genes could be switched on and off in specific parts of their

bodies, or in response to drugs placed in their drinking water, or

light flashed through fiber-optic cables. Not only did these tools

provide a better understanding of the genes and molecules associated

with disease, but they led to new approaches to research and

treatment—those involving human stem cells, for example—that might one

day make lab animals of any kind obsolete. The possibilities were

endless. What started as a lab animal had become the biologist's most

magnificent tinker toy.

Photograph from the World Health Organization.

As the power of the mouse model grew, researchers found fewer and

fewer reasons to study anything else. Even the stalwart lab rat began to

seem antiquated and unnecessary. (Genetic tools for the rat have been

much slower to develop; its first embryonic stem cells were created

in 2008, almost three decades after the same was accomplished in the

mouse.) In the 1990s, the National Institutes of Health placed the

transgenic lab mouse squarely at the vanguard of biomedical research—the

very model of the modern model animal. Under the leadership of Harold

Varmus, who won his Nobel Prize for using chicken and mouse cells to

identify the genes most susceptible to cancer-causing mutation, the NIH

announced that Mus musculus would be the second mammalian species to have its genome sequenced, after the human. "This animal is one of the most significant lab models for human disease," announced Varmus.

The government continued to support work on other organisms, as it

always had. "Everybody would prefer to work with the simplest, cheapest

system that can yield good results," Varmus explains by phone. "There's

no doubt that NIH is very sensitive to the need to help provide some

kind of support for developing [new] models." In 1997, he led an

NIH-wide effort to promote the study of zebra fish,

a kind of minnow that grows as a free-swimming, transparent embryo. Now

it's considered one of the most important models for research in

developmental biology and several other areas.

Varmus is also excited about new ways to study cells taken from human

tissue, healthy or diseased, and cultured in a dish. But when it came to

the genome project, and the most significant investment in living

animal models for biomedical research, the mouse was a clear favorite.

"It was chosen because not only was there a rich history of work," he

says, "but because we knew how to do two important things: We knew how

to add genes to the mouse germ line, and we knew how to manipulate genes

that were in the germ line."

The extraordinary tools available to mouse researchers—including the

ability to create transgenic animals and then stash their sperm and eggs

in freezers so they could be reproduced at will—made it possible to

envision a full catalog of gene knockouts, what Varmus calls an

"encyclopedic project" in biomedicine. "Everything you do with a mouse

is an approximation," he says, but scientists have now created tens of

thousands of kinds of mice, each one designed to answer its own set of

experimental questions. "We use these models in the hopes that we can

recapitulate human disease, and create a playing field for trying to

prevent and treat disease."

* * *

Microbiologist JoAnne Flynn has some concerns about mice, an inkling

that in some fields, at least, we may be too reliant on the standard

breeds. But if you ask her why she's been using them in her lab to study

TB for the last 20 years, she has no trouble rattling off an answer:

"They don't cough. They don't spread the disease. They live in small

cages. They're easy to infect by any route. …"

I ask her to slow down so I can catch up in my notes.

JoAnne Flynn, University of Pittsburgh School of MedicinePhotograph by by Joshua Franzos.

"… You can take out the lungs of four mice, and get very similar data

from each one. You can knock out any gene in the mouse, not in a guinea

pig or rabbit. You can turn a gene on for a little while and then turn

it off. You have every immunological reagent—all kinds of assays and

antibodies. …"

In her biosafety-level-3

laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh, Flynn has used the standard

animal model of TB to work out how particular elements of the immune

system fight off the disease. In 1995, for instance, she applied

knockout genes and monoclonal antibodies—two methods that were developed

in the mouse—to show that a signaling protein called TNF-alpha helps mice survive an infection for months, instead of weeks.

"… You can have mice of different genetic backgrounds, and determine

which genes make a difference. You can do vaccine studies. You can have

cells that turn certain colors. You can make T-cells turn yellow when

they do something. You can do trafficking studies, inject cells and

watch where they go. You can collaborate with people to make new kinds

of mice. …"

When she learned that doctors might prescribe TNF-inhibitors to

patients with autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, Flynn got

in touch with one of the pharmaceutical companies making the drugs. If

the mouse studies were right, she argued, then the treatment could be

dangerous—especially for patients who were carrying latent TB.

In 2001, researchers at Boston University and at the Food and Drug

Administration sifted through the database of adverse event reports for a

popular TNF-inhibitor, and found more than five dozen cases of

tuberculosis. The rate of infection among people taking the drug turned

out to be four times higher

than it was for other people of a similar health status. Twelve

patients had died from the disease. Flynn was right. The results were

published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

"… It may not be everything you want, but the mouse is a really

flexible model," she says, finally taking a breath. Among her

colleagues, the ratio of studies performed on mice to those using any

other species of lab animal is about 50-to-1. "A mouse is an extremely

reductive model, and it allows you to ask very specific questions," she

continues. The role of TNF-alpha is just one of its many contributions

to the study of tuberculosis: "The progress in TB research has been

astronomical. But there has been a reckoning. People have had to stop

and think, 'We're doing something wrong. We're not finding drug targets.

We're not finding drugs that work the way we think they're going to

work.' "

For Flynn, that reckoning came 10 years ago. She'd made a successful

career working out the details of tuberculosis immunology in the mouse.

But she knew that an effective, short-term treatment for latent TB—the

form of the disease that affects roughly one-third of the world's population—wasn't

going to emerge from studies like hers. The lab mice that she'd been

using since her first job as a post-doc, and that nearly every other

tuberculosis lab in the world had been using for decades, can only get

an active infection. "That's a huge downfall of the mouse," she says. "I

had to ask myself, am I missing something?"

If she wanted to study latent TB, she'd have to switch over to a new

lab animal—the crab-eating macaque. Monkeys contract tuberculosis as

humans do: Their lungs fill up with granulomas of different types and

structures, and in 60 percent of cases they sustain the infection with

no symptoms whatsoever. Converting her lab would be a daunting project,

though. Monkeys are many thousands of times more expensive to keep

around than mice, especially in the controlled environments used for the

study of infectious disease. It takes longer to finish monkey

experiments and publish monkey papers, which slows down the research as

well as the process of getting grants and otherwise advancing your

career. There's also the problem of small sample sizes, and the lack of

genetic tools and reagents. Flynn went ahead with her plan nonetheless,

and even after a decade's worth of monkey experiments she still spends

some of her time rehashing facts about TB—such as the role of CD4 immune

cells in containing the infection—that she'd established in the mouse

years ago. These are data that many of her colleagues would have

accepted without question. "It's incredibly risky and difficult for us,"

she says. "We took a leap."

Abandoning the mouse model may not be worth the time and money

required, says Richard Chaisson, director of the Center for TB Research

at Johns Hopkins University. "There are always questions about whether

new drugs will behave in the mouse in the same way old drugs do, but so

far nothing has come close to the accuracy of the mouse model for

telling us what to expect in people," he explains in an email. "There is

a great deal of interest in primate models right now, but there is no

current evidence that this very expensive approach is as good as, let

alone better than, the mouse."

Such evidence would be hard to come by. It's not clear how one might

prove, in a satisfying and scientific way, that any given lab animal is

better than another. We can't go back and spend the last 50 years

studying monkeys instead of mice, and then count how many new drugs came

as a result. The history of biomedicine runs in one direction only:

There are no statistics to compare; it's an experiment that can't be

repeated.

Before the mouse started to take over the field in the 1960s, the

classical models for TB research were rabbits and guinea pigs—small,

cheap mammals with a granulomatous response that's not too far off from

what happens in humans. Since then, a number of new models have emerged:

Goldfish and frogs develop a very similar disease, and so can the zebra fish,

the minnow championed by the NIH: Its granulomas can be seen forming in

real time. Flynn sees a place in the field for every one of these

models. Different questions require different methods, she says. But if

you want to study the course of latent TB in an animal host, than you're

stuck with macaques or another nonhuman primate.

As for mice, "it's not that [they] aren't useful," she says, "or even that they're not the most useful possible system. Rather, it's that by focusing only on the mouse, we're running a grave risk."

For a scientist, switching lab animals in the middle of your career

is something like changing religions. The academic world tends to

cluster by model system: "Mouse people" talk to mouse people; "monkey

people" talk to monkey people; each group exists within its own fibrous

granuloma of meetings, conferences and review committees. When you

submit a grant application to the NIH, or a manuscript to a scientific

journal, the peers who assess your work are likely to be fellow

travelers, members of your animal clique. Changing over from one species

to another means backing out of a social sphere, and when the sphere

you're leaving happens to be the biggest and best-funded, well: "I used

to lose sleep over this," Flynn tells me at one point. And then later,

with a chuckle: "I always say it's career suicide."

* * *

Clif Barry, the man of the Germantown menagerie, seems like he knows

the value of standardization. When I meet him in his office at the

National Institutes of Health in July, he's wearing a pair of black

pants, a black belt, and black socks; a tight-fitting black polo shirt

and a pair of black, rectangular eyeglasses from Armani Exchange;

there's a pair of black sneakers beside him on the floor. The monochrome

wardrobe makes life easier, he tells me. Everything matches everything

else. It's one less thing to worry about.

Yet Barry has moved away from the standard model for tuberculosis

research—the one that can be ordered by phone, hundreds at a time, in

well-characterized strains and breeds. Like JoAnne Flynn, he's rejected

the animal that allows for the most intricate molecular manipulations,

and the most rapid screenings of new drugs. For him, the vaunted

efficiencies of the murine-industrial complex are an illusion. Drugs go

from mice to man, and then they fail.

A marmoset at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Courtesy of the Tuberculosis Research Section, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Courtesy of the Tuberculosis Research Section, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

In his own lab, he's spent the last three years working out what he

calls an "advanced model" for drug-discovery—a brown-eyed primate with

tufts of white poking from above its ears, and mottled, black-and-gray

fur. At 7 inches in length, and weighing just half a pound, a marmoset

isn't any bigger than a lab rat, and it reaches sexual maturity in half

the time it takes a macaque. Around 90 percent of all marmoset births

result in chimeric siblings

with matching immune systems, which give Barry an easy way to control

each experiment: It's like he's running a series of tiny twin studies.

One marmoset gets a new drug and its littermate doesn't; then he

compares the results. There's even hope that the marmoset might be

susceptible to wholesale genetic engineering: In 2009, a Japanese team created a transgenic line of marmosets—the first time that had ever been accomplished in a primate species.

Compared with mouse research, though, Barry's advanced model moves at

a glacial pace. His animals need 35 times more space than mice, and

round-the-clock veterinary care. They're contagious, so lab workers have

to wear puffy biohazard suits with built-in fans. And each animal must

be trained laboriously to accept drug injections and crawl into a CT

scanner. In all, says Barry, the switch to marmosets has reduced the

number of compounds he can test in the lab by a factor of 50 or 100.

"I'm continuously second-guessing it," he admits. Could a slower, less

efficient animal model really help us cure tuberculosis?

Barry is betting that it can, but there's an eminence grise

standing against him: 82-year-old doctor and microbiologist Jacques

Grosset. A Frenchman with fluffy, white hair, Grosset has been training

the next generation of TB researchers for the last half-century,

screening new drugs and combination therapies in a strain of inbred

mouse called the Bagg's Albino. They infect and inject hundreds of them at a time, in an ongoing parade of pale ears, pink eyes, and matching snow-white coats.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, Grosset participated in the development of the

classic, four-drug treatment for TB; since then, he's run his mice

through various tweaks and substitutions that might improve the therapy.

Some of these have turned out more useful than others. In 1989, he

observed that one of the ingredients in the cocktail seemed to be

spoiling the mix: Infected lab mice were better off when he removed it altogether.

Fifteen years later, Grosset's team made another big discovery: When

they replaced the troublesome drug with a new one called moxifloxacin,

their mice were cured in record time. "The findings suggest that this

regimen has the potential to substantially shorten the duration of therapy needed to cure human tuberculosis," they wrote.

The video above shows lung scans from

twin marmosets with tuberculosis. The sibling on the left suffers from a

more virulent strain of the disease known as the "Beijing clade," which

may be especially dangerous to humans. The distinction is invisible in

mouse models.

Barry considers Grosset a friend—he even named one of his frizzy-haired bichon frises Jacques

in his honor—but he was skeptical when the moxifloxacin finding was

announced at a lung-disease conference in Paris. Everyone was talking

about how to get Grosset's new regimen into the clinic as quickly as

possible, but there wasn't much reason to think the mouse data would

translate to humans. "People were going wild; it was a frenzy. And I

stood up at the microphone and said, 'This is a mistake. It's going to

fail. And when it fails, I don't want to hear anything more about the

mouse model.' "

No one listened. A major trial soon followed, enrolling more than 400

patients from 26 hospitals on four continents—the kind of research that

typically runs tens of millions of dollars—and, sure enough, the

results were disastrous. Swapping in the new drug had no observable

effect on the course of treatment. When the scientists in charge,

Grosset among them, published their report in 2009, they could only

scratch their heads over "the apparent discordance between murine results and results of this clinical study."

A second group ran a very similar, and similarly expensive, clinical

trial shortly thereafter, this time focusing on TB in American and Asian

patients, rather than the Black Africans who predominated in Grosset's

study. The results were more or less the same. "We keep getting led down

the garden path," Barry argues. The doctors who devised the classic

treatment 40 years ago didn't need detailed mouse data—they found their

cure with a methodical, brute-force approach: a series of human trials

that spanned the better part of two decades and tested every possible

combination of exposures. "The way those four drugs were put together is

incredible. It's never to be seen again."

Since that happened, we've had thousands of mouse studies of

tuberculosis, yet not one of them has ever been used to pick a new drug

regimen that succeeded in clinical trials. "This isn't just true for TB;

it's true for virtually every disease," he tells me. "We're spending

more and more money and we're not getting more and more drug

candidates."

* * *

Clif Barry is not the only scientist frustrated by the pace of

progress. It's not at all clear that the rise of the mouse—and the

million research papers that resulted from it—has produced a revolution

in public health.

It's hard to measure such things in aggregate, of course, but science

and health policymakers have reached an uneasy consensus on this fact:

We're at a moment of crisis in drug discovery. Last winter, current NIH

director Francis Collins established a new institute (his agency's 28th)

to address the "pipeline problem" in biomedicine: Despite pouring

billions of dollars into research every year, our rate of innovation has

slowed to a trickle. It takes more than a decade, and some $800

million, to produce a viable, new drug; among the compounds considered

for testing, only 1 in 10,000 come to fruition.

These are grim statistics, the kind that get bandied about in

discussions of health care reform and the national budget deficit. We've

seen a revolution in molecular genetics, yet medical research has been spinning down to a halt. The United States spends more than twice as much

on the health of its citizens as do most Western nations, yet ranks

middling to poor on life expectancy, infant mortality, cancer survival

rates, and many other important measures. No one knows why.

Some worry that with all our fine-tuned genetic methods, we've gotten hung up on the small-scale workings of disease.

It's missing the forest for the trees, goes the argument: Doctors did

better in the 1970s, when they tried to find drugs that worked in the

clinic, regardless of the mechanism. Others acquit the basic science,

but say our clinical trials—the human tests—are run so poorly that good

drugs, safe and effective ones, are flunking out. Another group wonders

if we're getting held up at the preclinical stage: Researchers may be using shoddy statistical methods in their animal work,

or scrapping negative results, or even adding subtle bias to their data

when they pluck certain mice from the cage instead of others.

Here's another way to explain the heavy expense and slow rate of

return in biomedicine: Maybe the animals themselves are causing the

problem. Assembly-line rats and mice have become the standard vehicles

of basic research and preclinical testing across the spectrum of

disease. It's a one-size-fits-all approach to science. What if that one

size were way too big?

For some maladies, like tuberculosis, the rodent model may be

inadequate to its core, lacking in the basic mechanisms of human

disease. For others, the mere fact of the rodents' ubiquity—and the

standard ways in which they're used—could be hindering research. Jeffrey

Mogil, who studies chronic pain at McGill University in Montreal,

points out that almost every datum of mouse research comes from male

specimens, despite the fact that male and female mice respond to pain in

different ways. Mark Mattson laments the factory breeding conditions

and mass-husbandry practices that bias his experiments and leave his

control animals overfed and unwell.

Perhaps the researchers have come to resemble their favored species:

So complacent and sedentary in their methods, so well-fed on government

grants, that any flaws in the model have gone unnoticed, sliding by like

wonky widgets on a conveyor belt. It could be that the investigators

and the investigated are locked together in the mindless machinery of

science, joined hand and paw in the manufacture of knowledge. If there

were something wrong with the rodent—not just its body weight or

exercise habits, but in its fundamental utility as an instrument of

learning—the scientists may not realize it at all.

It might take an outsider to see the problem, then, someone standing

beyond the factory gates. Starting in the early 1990s, and coincident

with the rise of the transgenic mouse, a set of historians and

philosophers of science began to construct a formal critique

of industrial biomedicine. They acknowledge, first of all, that the

mouse and rat have been enormously productive, and that standardization

brought with it unparalleled economies of scale. But they wonder whether

a laboratory monoculture, with such a glut of cheap data, can be truly

sustainable. Rats and mice were never so good at curing disease as they

were at making data for its own sake: We have a million papers' worth

already, and could soon have a million more: experimental results that

might one day be mothballed in dusty stacks, next to those of some other

research juggernauts—phrenology, miasmatism, radical behaviorism—that rolled along for decades before coming to a creaking halt, not so useful and not much cited.

Whether the critics are paranoids or prophets, the hordes of mice are

marching on. Transgenic models have colonized the whole of biomedicine,

and their influence grows daily. At a meeting in London last year,

scientists announced the inevitable next step—an audacious plan to

mutate every single gene in the murine genome and record the function of

each one in a public database. It’s a massive, multigovernment

undertaking that would reinforce the mouse's position as the most

thoroughly examined and explicated higher organism on the planet—“a

historic opportunity,” as one of its organizers, Mark Moore, describes

it, “to systematically learn everything about a mammal for the first time.”

The project, which has the support of science agencies in the United

States and Europe, will cost at least $900 million. That is to say it’s a

monumental piece of megascience with a price tag on the order of the

Large Hadron Collider. In the end, we’ll have an archive of stem cell

lines—a community warehouse from which researchers can create (and order

off the Web) an animal with any one of its 20,000 genes inactivated.

And each of those myriad versions of the mouse will have been run

through a standard battery of tests and had its essential features

stored in a public database.

A bio-utopian dream like this can imprison us with grand

expectations. Once you've invested so much into a single model, how do

you know when that model's utility has run its course and it's time to

move on? Vinny Lynch, an evolutionary biologist at Yale University, has a

quixotic vision for the future of biology. It's the "hourglass model"

of animal research: We started out in what was almost the random study

of nature—a broad biology of birds and snails and elephants, uninformed

by deeper understanding. Then came the narrowing of the 20th

century, when all our research efforts were funneled through a slender

sieve of model systems. Now we've reached the limit of that

bottleneck—the inherent limitations of the mouse, let's say—and it's

time to broaden out once more, to apply all the knowledge we've gained

over the last hundred years to selecting new animals and new systems,

and broaden out into a more rational, relevant science.

In a paper titled "Use with caution: Developmental systems divergence and potential pitfalls of animal models,"

Lynch makes the argument for entering this next phase. He tells me we

may already have reached a tipping point, in fact. The mouse monopoly is

teetering in the face of cheaper, faster genetic technologies. More and

more species are having their genomes sequenced and their DNA

manipulated in the lab. In a hamlet on the north shore of Long Island,

the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory keeps track of where we might be

headed. Its Website declares, "the variety of organisms studied is currently undergoing a massive expansion."

Among the emerging models profiled on the site are the wallaby and the

wasp, the quail and the snail, the yam and the snapdragon.

These are encouraging indicators. They suggest that, in spite of the

billion-dollar mouse mutation project now on the horizon, we may soon

find ourselves backing away from the industry standards that have

dominated biomedical research for so many decades. Clif Barry and JoAnne

Flynn may be at the vanguard of a new movement within science, a

retreat from the seductions of model organism-ism to something more diverse—a throwback, perhaps, to the slower, more comparative style of the 19th century, when theories were constructed from the differences among the many, rather than the similarities of a few.

Every standard organism has its limit, some finite store of knowledge

that can be gleaned from it. There will come a point when we’ll have

learned so much about the workings of a mouse, and dissected its every

organ in such nanoscopic detail, that its veins of data run dry. There's

a depth at which the science begins to founder, where its explorations

become so profound and so specific, so lost in the letters of a foreign

genome, that its reports to the academy no longer mean anything at all.

To move beyond this dead end, to develop new treatments for disease and

understandings of how it works, we'll need a more inclusive science, a

more organic science, a research enterprise with room

for mice and flies and worms, but marmosets, too—all the bugs and birds

and beasts that live together in a vibrant ecosystem of discovery.

No comments:

Post a Comment