Having It All. In France. 100 Years Ago.

Turns out the work-life balance debate was raging in Belle Époque magazines, too.

At first blush, recent discussions about women “having it all” seem

to be uniquely American and of this time: the product of our

overachieving society, capitalism, and the constant pressure to succeed.

But it’s also a product of the mass media and its particular, visual

pressures upon women. This, then, is not a new phenomenon. It actually

originated more than 100 years ago in France, where both photography and

film were invented, and arguably celebrity culture as well (think Sarah

Bernhardt).

Photo courtesy Rachel Mesch.

Around the time that photographs of famous people were first starting

to circulate in French magazines, these magazines were also reimagining

how to present the modern French woman. In the early 1900s, rival

publications Femina and La Vie Heureuse (literally, The Happy Life) introduced the femme moderne,

a much more pleasing spectacle than her predecessors, who had for years

been the bicycle-riding, pants-wearing, cigarette-smoking,

husband-chastising “New Woman” (quite the media construction herself).

The femme moderne was a beautiful creature who could

perfectly—and joyfully—balance femininity and feminism, without so much

as breaking a sweat. All of a sudden, women’s progress was not about

making demands but about performance and possibility, evidenced by an

array of photographs that repeatedly demonstrated the elegant and

graceful ways that women were embracing modern roles. This offered women

a pleasing, affirming, and celebratory new way to see themselves— both a

great feminist strategy and a fabulous way to sell more magazines.

Corsets were already on their way out in 1911 when this ad appeared in La Vie Heureuse, coyly affirming the link between feminism and femininity at the core of the femme moderne

identity. This manufacturer advertised a gentler, healthier corset—the

product of the latest medical research—which would avoid “suffering or

wounds to internal organs” while offering perfect alignment.

Photo courtesy Rachel Mesch.

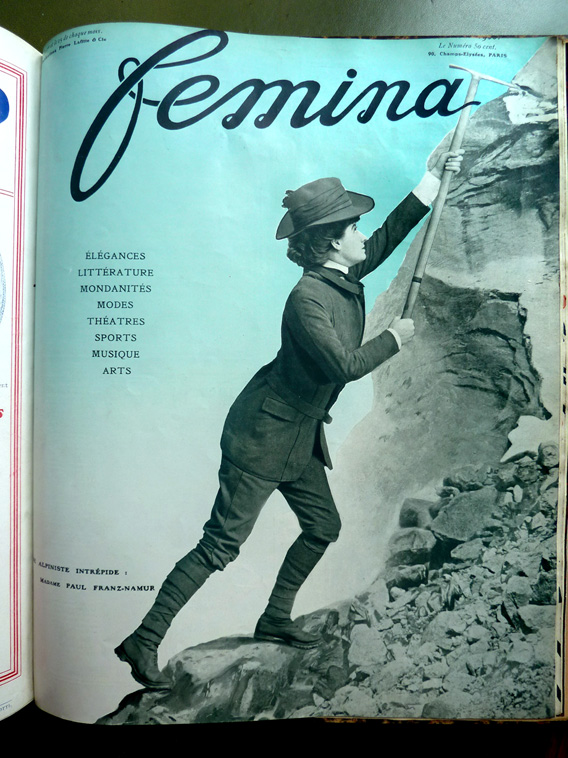

With rapidly evolving photographic technology, Femina was

able to feature images that represented impressive feats while

suggesting metaphorical possibilities. While this woman was actually

climbing a mountain, women readers were subtly urged to reach new

heights themselves.

Photo courtesy Rachel Mesch.

Who says women are subject to vertigo? asks the caption. Here’s evidence to the contrary!

Like the mountain climber, this woman literalizes the message of female

achievement at the highest level and seems miraculously unhindered by

her flowing skirts.

Photo courtesy Rachel Mesch.

Sports journalism was all the rage in the 1900s, thanks to portable,

wide-angle cameras that could capture action shots. For the first time,

you didn’t have to attend an event to catch its highlights. Femina and La Vie Heureuse

frequently featured women athletes, appropriately dressed. This tennis

player looks happy, celebratory, and strong without losing her

femininity in the process.

Photo courtesy Rachel Mesch.

Roller skating was the hottest new sport for women in 1911. The expression on the face of this rinkeuse—a former dancer—as well as her graceful pose captures it all: She’s skating straight into a freer, more joyful future.

Photo courtesy Rachel Mesch.

Educational reforms in the late 1880s meant that more women were

entering professions than ever before, but there were still only a

handful of female doctors and lawyers. A later Femina article zeroed in on one of these young women, who chose her profession, bien sur,

in order to help other women and children. They described her as “tall

and thin, confident, and wearing a lovely red dress that fit simply

under her robe.”

Photo courtesy Rachel Mesch.

Driving was described in the magazine both as a sporty, modern

activity and a way to expand women’s domain beyond the homefront. And

while the independent, family-unfriendly New Woman was associated with

the bicycle—a vehicle rumored to cause both self-pleasuring and

infertility—the car had room for kids in the back.

Photo courtesy Rachel Mesch.

Royals were among the first celebrities. Readers loved to admire

their exquisite furniture and fashions but also to see that, as women,

they were “just like us.” Babies were the perfect equalizer—and really,

is there anything more compelling than the image of a queen giving her

son a piggy-back ride?

Photo courtesy Rachel Mesch.

On the other hand, it wasn’t enough to just be royalty

anymore. Even queens had to do more to impress a new generation of

achieving women. When the queen of Romania published a poetry collection

in French, she became a literary sensation. This issue of the magazine

announced the first of a series of writing contests that would lead to

the Prix Femina, distinguished by its all-female jury, and to this day is one of the most coveted literary awards in France.

Photo courtesy Rachel Mesch.

Female writers were among the magazine’s most beloved celebrities.

Media darling Lucie Delarue-Mardrus became famous because her husband (a

famous writer himself) had the good sense to send in photos of her in

exotic costumes while they were traveling in Tunisia—a natural hit for a

French public infatuated with the Orient. When she returned to Paris a

few months later with a new poetry collection, Delarue-Mardrus was

already in high demand.

Photo courtesy Rachel Mesch.

In 1909, the Académie française took up the question of electing female members. In the meantime Femina

asked readers to elect 40 women writers, past or present, to fill a

fictional female academy. This primitively photoshopped image imagines

the winners in the halls of the venerable institution. Despite the

optimism of the moment, a woman wouldn’t be elected into the Académie française until 1980(!).

Photo courtesy Rachel Mesch.

This striking cover by the beloved artist Paul Cesar Helleu

assimilated breast-feeding with traditional French elegance. Some of the

most popular women’s fiction of the time discussed the challenges of

nursing for the female professional. Sound familiar? In a 1909 novel, a

rising legal star runs off to nurse in between court sessions; in

another, the protagonist is a brilliant doctor whose child dies after

the nanny adds water to breast milk while Maman is off seeing patients.

Photo courtesy Rachel Mesch.

In spite of celebrated novelist Marcelle Tinayre’s slightly

awkward—and surely untenable!—pose, the caption on this photo leaves no

room for doubt on its intentions: “Between the started manuscript and

the child to whom she gives her hand, Madame Tinayre—even while

composing wonderful books— has maintained the very spirit of feminine

life—a tender heart, love for little ones, the taste for decorating her

home.” Compare this image with Tina Fey’s eerily similar American Express ad (which suggests what might happen if Tinayre let go). Plus ça change?

Photo courtesy Rachel Mesch.

Photo courtesy Rachel Mesch.

No comments:

Post a Comment