|

| Attic red-figure kylix dish, dated 510BC, Louvre Musuem. |

Monday, December 31, 2012

Talk about running out of ideas...this shits getting old

Sunday, December 30, 2012

Saturday, December 29, 2012

Nobuyoshi Araki

yes

Education is the Work of Teachers, not Hackers

Washington Diarist.

- December 21, 2012 | 12:00 am

Joe Corrigan/Getty Images Entertainment/Getty Images

WHEN

I LOOK BACK at my education, I am struck not by how much I learned but

by how much I was taught. I am the progeny of teachers; I swoon over

teachers. Even what I learned on my own I owed to them, because they

guided me in my sense of what is significant. The only form of knowledge

that can be adequately acquired without the help of a teacher, and

without the humility of a student, is information, which is the lowest

form of knowledge. (And in these nightmarishly data-glutted days, the

winnowing of information may also require the masterly hand of someone

who knows more and better.) Yet the prestige of teachers in America

keeps sinking. In the debate about the reform of the public schools, the

virulent denigration of teachers is regarded as advanced opinion. The

new interest in homeschooling—the demented idea that children can be

competently taught by people whose only qualifications for teaching them

are love and a desire to keep them from the world—constitutes another

insult to the great profession of pedagogy. And now there is the fashion

in “unschooling,” which I take from a forthcoming book by Dale J.

Stephens, the gloating founder of UnCollege. His deeply unfortunate book

is called Hacking Your Education: Ditch the Lectures, Save Tens of Thousands, and Learn More Than Your Peers Ever Will.

It is a call for young people to reject college and become

“self-directed learners.” One wonders about the preparedness of this

untutored “self” for this unknown “direction.” Such pristinity! Rousseau

with a MacBook! Yet the “hackademic,” as Stephens calls his ideal, is a

new sort of drop-out. His head is not in the clouds. His head is in the

cloud. Instead of spending money on college, he is making money on

apps. In place of an education, he has entrepreneurship. This preference

often comes with the assurance that entrepreneurship is itself an

education. “Here in Silicon Valley, it’s almost a badge of honor [to

have dropped out],” a boy genius who left Princeton and started Undrip

(beats me) told The New York Times. After all, Jobs, Gates,

Zuckerberg, and Dell dropped out—as if their lack of a college education

was the cause of their creativity, and as if there will ever be a

generation, or a nation, of Jobses, Gateses, Zuckerbergs, and Dells.

Stephens’s book, and the larger Web-inebriated movement to abandon study

for wealth, is another document of the unreality of Silicon Valley, of

its snobbery (tell the aspiring kids in Oakland to give up on college!),

of its confusion of itself with the universe. To be sure, all learning

cannot be renounced in the search for success. Technological innovation

demands scientific and engineering knowledge, even if it begins in

intuition: the technical must follow the visionary. So the movement

against college is not a campaign against all study. It is a campaign

against allegedly useless study—the latest eruption of the utilitarian

temper in the American view of life. And what study is allegedly

useless? The study of the humanities, of course.

THE MOST EGREGIOUS of the many errors in this repudiation of college is its economicist approach to the understanding of education. We have been here before. Not long ago Rick Santorum, if you’ll pardon the expression, delivered himself of this tirade: “I was so outraged by the president of the United States for standing up and saying every child in America should go to college. ... Who are you to say that every child in America go? I, you know, there is—I have seven kids. Maybe they’ll all go to college. But if one of my kids wants to go and be an auto-mechanic, good for him. That’s a good paying job.” He was responding wildly to Barack Obama’s proposal that “every American ... commit to at least one year of higher education or career training. This can be community college or a four-year school; vocational training or an apprenticeship.” Obama was not forcing Flaubert down a single blue-collared throat. Indeed, Obama and Santorum were regarding education from the same stunted standpoint: the cash nexus, or the problem of American “competitiveness.” A few months later, the Council on Foreign Relations published another instrumentalist analysis, equally uncomprehending about the horizons of the classroom, called “U.S. Education Reform and National Security,” which proposed, among other things, that the liberal arts curriculum be revised to give priority to “strategic” languages and “informational” texts. As Robert Alter acerbically remarked, in a devastating issue of the Forum of the Association of Literary Scholars, Critics, and Writers, this is “Gradgrinding American education”: “there is no place whatever in this purview for Greek and Latin, because you can’t cut a deal with a multinational in the language of Homer or Virgil.”

THE PRESIDENT IS RIGHT that we should “out-educate” other countries, but he is wrong that we should do so only, or mainly, to “out-compete.” Surely the primary objectives of education are the formation of the self and the formation of the citizen. A political order based on the expression of opinion imposes an intellectual obligation upon the individual, who cannot acquit himself of his democratic duty without an ability to reason, a familiarity with argument, a historical memory. An ignorant citizen is a traitor to an open society. The demagoguery of the media, which is covertly structural when it is not overtly ideological, demands a countervailing force of knowledgeable reflection. (There are certainly too many unemployed young people in America, but not because they have read too many books.) And the schooling of inwardness matters even more in the lives of parents and children, husbands and wives, friends and lovers, where meanings are often ambiguous and interpretations determine fates. The equation of virtue with wealth, of enlightenment with success, is no less repulsive in a t-shirt than in a suit. How much about human existence can be inferred from a start-up? Shakespeare or Undrip: I should have thought that the choice was easy. Entrepreneurship is not a full human education, and living is never just succeeding, and the humanities are always pertinent. In pain or in sorrow, who needs a quant? There are enormities of experience, horrors, crimes, disasters, tragedies, which revive the appetite for wisdom, and for the old sources, however imprecise, of wisdom—a massacre of schoolchildren, for example.

Leon Wieseltier is the literary editor of The New Republic. This article appeared in the December 31, 2012 issue of the magazine under the headline “The Unschooled.”

THE MOST EGREGIOUS of the many errors in this repudiation of college is its economicist approach to the understanding of education. We have been here before. Not long ago Rick Santorum, if you’ll pardon the expression, delivered himself of this tirade: “I was so outraged by the president of the United States for standing up and saying every child in America should go to college. ... Who are you to say that every child in America go? I, you know, there is—I have seven kids. Maybe they’ll all go to college. But if one of my kids wants to go and be an auto-mechanic, good for him. That’s a good paying job.” He was responding wildly to Barack Obama’s proposal that “every American ... commit to at least one year of higher education or career training. This can be community college or a four-year school; vocational training or an apprenticeship.” Obama was not forcing Flaubert down a single blue-collared throat. Indeed, Obama and Santorum were regarding education from the same stunted standpoint: the cash nexus, or the problem of American “competitiveness.” A few months later, the Council on Foreign Relations published another instrumentalist analysis, equally uncomprehending about the horizons of the classroom, called “U.S. Education Reform and National Security,” which proposed, among other things, that the liberal arts curriculum be revised to give priority to “strategic” languages and “informational” texts. As Robert Alter acerbically remarked, in a devastating issue of the Forum of the Association of Literary Scholars, Critics, and Writers, this is “Gradgrinding American education”: “there is no place whatever in this purview for Greek and Latin, because you can’t cut a deal with a multinational in the language of Homer or Virgil.”

THE PRESIDENT IS RIGHT that we should “out-educate” other countries, but he is wrong that we should do so only, or mainly, to “out-compete.” Surely the primary objectives of education are the formation of the self and the formation of the citizen. A political order based on the expression of opinion imposes an intellectual obligation upon the individual, who cannot acquit himself of his democratic duty without an ability to reason, a familiarity with argument, a historical memory. An ignorant citizen is a traitor to an open society. The demagoguery of the media, which is covertly structural when it is not overtly ideological, demands a countervailing force of knowledgeable reflection. (There are certainly too many unemployed young people in America, but not because they have read too many books.) And the schooling of inwardness matters even more in the lives of parents and children, husbands and wives, friends and lovers, where meanings are often ambiguous and interpretations determine fates. The equation of virtue with wealth, of enlightenment with success, is no less repulsive in a t-shirt than in a suit. How much about human existence can be inferred from a start-up? Shakespeare or Undrip: I should have thought that the choice was easy. Entrepreneurship is not a full human education, and living is never just succeeding, and the humanities are always pertinent. In pain or in sorrow, who needs a quant? There are enormities of experience, horrors, crimes, disasters, tragedies, which revive the appetite for wisdom, and for the old sources, however imprecise, of wisdom—a massacre of schoolchildren, for example.

Leon Wieseltier is the literary editor of The New Republic. This article appeared in the December 31, 2012 issue of the magazine under the headline “The Unschooled.”

Friday, December 28, 2012

Philip Guston- 1968

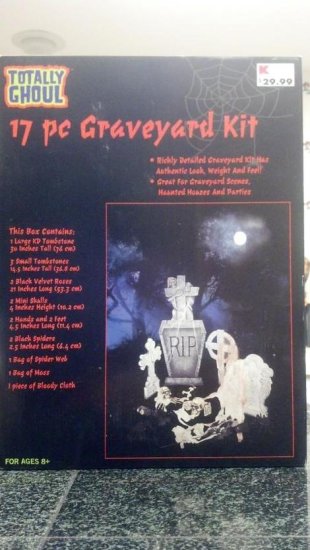

Letter from Chinese Laborer Pleading for Help Found in Halloween Decorations

By Jessica Ferri | Work + Money – 2 hours 12 minutes ago This letter was found in Halloween decorations purchased from KmartJulie Keith was unpacking some of last year's Halloween decorations when she stumbled upon an upsetting letter wedged into the packaging.

This letter was found in Halloween decorations purchased from KmartJulie Keith was unpacking some of last year's Halloween decorations when she stumbled upon an upsetting letter wedged into the packaging.

Tucked in between two novelty headstones that she had purchased at Kmart, she found what appeared to be a letter from the Chinese laborer, who had made the decoration, pleading for help.

Samsung in hot seat over abusing Chinese workers

The letter reads: "Sir, if you occasionally buy this product, please kindly resend this letter to the World Human Right Organization. Thousands people here who are under the persicution of the Chinese Communist Party Government will thank and remember you forever."

"I was so frustrated that this letter had been sitting in storage for over a year, that this person had written this plea for help and nothing had come of it." Julie Keith told Yahoo! Shine. "Then I was shocked. This person had probably risked their life to get this letter in this package."

The letter describes the conditions at the factory: "People who work here have to work 15 hours a day without Saturday, Sunday break and any holidays. Otherwise, they will suffer torturement, beat and rude remark. Nearly no payment (10 yuan/1 month)." That translates to about $1.61 a month.

The letter was found inside this packagingKeith,

a mom who works at the Goodwill in Portland, Oregon, did some research

into the letter. "I looked up this labor camp on the internet. Some

horrific images popped up, and there were also testimonials about people

who had lived through this camp. It was just awful."

The letter was found inside this packagingKeith,

a mom who works at the Goodwill in Portland, Oregon, did some research

into the letter. "I looked up this labor camp on the internet. Some

horrific images popped up, and there were also testimonials about people

who had lived through this camp. It was just awful."Horrified, Keith took to Facebook. She posted an image of the letter to ask friends for advice. One responded with a contact at Amnesty International. Keith made several attempts to alert them about the letter, but the organization never responded.

This is not the first time a letter like this has turned up. Just this week, another plea was found written in Chinese on a toilet seat and posted on Reddit. Commenters on the website have questioned the letters' authenticity.

Though the letter lists the address of the specific camp, officials at Human Rights Watch were unable to verify the authenticity of the letter. However, Sophie Richardson, China director at Human Rights Watch, told The Oregonian that the description was consistent with their research. "I think it is fair to say the conditions described in the letter certainly conform to what we know about conditions in re-education through labor camps."

The concern over the conditions laborers must endure in China and other countries first came to the public eye in the 1980s with the use of sweatshops to make Nike sneakers. Since then, according to an article recently published in The New York Times, Nike "has convened public meetings of labor, human rights, environmental and business leaders to discuss how to improve overseas factories."

Tech companies, like Apple and Hewlett Packard, are being made to be accountable for their labor practices. After receiving a great deal of criticism, Apple is now making public statements that they are aware of the harsh conditions in China and are taking steps to improve them.

As for Julie Keith, she had a general idea about the conditions in Chinese labor camps, but this letter has been a dramatic eye-opener into the stark reality of the issue. "I was aware of labor camps. I knew they had factories but I had no idea of the gravity of the situation. I didn't realize how bad it could be for people."

Finding the letter has made Keith more aware of the origin of many products sold in the United States. "As I was doing my Christmas shopping this year, I checked every label. It's virtually impossible to avoid purchasing things made in China as over 90 percent of our goods are made there. But if I saw 'made in China,' this year I asked myself, 'do I really need this?'"

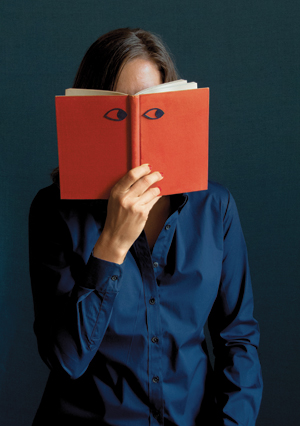

Secret Lives of Readers

By Jennifer Howard

Illustration by Stephen Doyle for The Chronicle

How do we recover the reading experiences of the past? Lately scholars have stepped up the hunt for evidence of how people over time have interacted with books, newspapers, and other printed material.

"You're looking for teardrops on the page," says Leah Price, a professor of English at Harvard University and the author of How to Do Things With Books in Victorian Britain (Princeton University Press, 2012). "You're looking for some hard evidence of what the book did to its reader"—and what the reader did with the book.

Price's work perches at the leading edge of a growing body of investigations into the history of reading. The field draws from many others, including book history and bibliography, literary criticism and social history, and communication studies. It looks backward to the pre-Gutenberg era, back to the clay tablets and scrolls of ancient civilizations, and forward to current debates about how technology is changing the way we read. Although much of the relevant research has centered on Anglo-American culture of the last three or four centuries, the field has expanded its purview, as scholars uncover the hidden reading histories of cultures many used to dismiss as mostly oral.

It's a tricky business. A bibliographer works with hard physical evidence—a manuscript, a printed book, a copy of the Times of London. A scholar seeking to pin down the readers of the past often has to read between the lines. Marginalia can be a gold mine of information about a book's owners and readers, but it's rare. "Most of the time, most readers historically didn't, and still don't, write in their books," Price explains.

"The history of reading," Price says, "really has to encompass the history of not reading."

Anyone who has ever displayed a trophy volume on the coffee table knows that people do many things with books besides read them. A book can be deployed as a sign of intellectual standing or aspiration. It can be used to erect a social barrier between spouses at a breakfast table or strangers on a train. It can be taken apart and recycled or turned into art. Price's recent work recreates Victorians' many extratextual uses of books.

Earlier work involving reader-reception theory and book history helped point the way toward current investigations of readers and reading. In 1984, a prominent literary critic and cultural-studies professor, Janice Radway, published a groundbreaking study, Reading the Romance, which investigated how reading genre novels helped a group of contemporary women in the Midwest cope with the demands and strictures of their lives. Radway, a professor of communication studies at Northwestern University, went on to write A Feeling for Books, about the Book-of-the-Month Club and middle-class literary sensibilities, and co-wrote a volume of a multipart history of the book in America.

Since Reading the Romance, the ethnography of reading has taken off among scholars. Radway points to Forgotten Readers, Elizabeth McHenry's study of African-American literary societies, Ellen Gruber Garvey's Writing With Scissors, about scrapbooking, and David Henkin's City Reading, about signage in the urban environment, as strong examples. "People have become very creative about trying to figure out how groups of readers interact with the text as it's embodied in various forms," she says.

Historians of the book have had a substantial influence on the development of the history of reading. For instance, in 1996, Robert Darnton, a historian of 18th-century France, published The Forbidden Best-Sellers of Pre-Revolutionary France, in which he argued that surreptitious reading of banned books helped set off the powder keg of the French Revolution. Darnton, now the director of libraries at Harvard University, has published a number of other influential works on publishing history and the uses of books.

In 2001, Jonathan Rose, a professor of history at Drew University, upended assumptions about what nonelite Britons did and didn't read in The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes. Rose, who co-founded the Society for the History of Authorship, Reading, and Publishing, is now at work on a study of Winston Churchill's reading, how it shaped him, and how reading Churchill in turn influenced younger politicians, including John F. Kennedy.

Scholars have also been moving the history of reading beyond the Anglo-American context. In 2003, Isabel Hofmeyr, a professor of African literature at the University of Witwatersrand, in South Africa, published The Portable Bunyan, which examined Pilgrim's Progress as a "transnational book" that found readers around the world, including in sub-Saharan Africa. This year Archie L. Dick, a professor of information science at the University of Pretoria, published The Hidden History of South Africa's Book and Reading Cultures (University of Toronto Press).

While the history of the book is well established, the history of reading has really come together in the last two decades, according to Shafquat Towheed, a lecturer in English at the Open University in Britain and director of the Reading Experience Database, or RED. "We're beginning to get students studying it as an option at the graduate level and the undergraduate level," Towheed says.

The existence of online resources such as RED has helped push the field along. The brainchild of Simon Eliot, another influential figure in the history of reading, RED dates back to the 1990s but was revamped as an online resource in 2006.

The Bridgeman Art Library

"The Travelling Companions," by Augustus Leopold Egg (1862)

The open-access database collects accounts of British reading experiences from 1450 to 1945, and has gathered about 31,000 records so far. "British" includes anyone born or living in Britain during that period. Users can search by keyword, reader, or author. Each entry gives the date of the reading experience, as closely as it can be pinpointed; where it took place (in London, in a house, etc.); who was reading (age, gender, occupation, and so forth); what they were reading; whether they were alone or in company.

One especially rich source has been the Proceedings of the Old Bailey, London's central criminal court, whose records from 1674 to 1913 have recently been put online. Another important source is Henry Mayhew's London Labour and the London Poor, an epic multivolume account published by the journalist in 1851 based on his investigations into how the city's working and poorer classes lived.

Roaming through such material brings the experiences of past readers alive. In a Reading Experience Database-related essay on "Reading Culture in the Victorian Underworld," Rosalind Crone, a lecturer in history at the Open University, recounts a couple of anecdotes from Mayhew's forays among less fortunate Londoners: "The crippled penny mousetrap maker, 'for an hour's light reading,' turned to Milton's Paradise Lost and Shakespeare's plays. And a sweet-stuff maker bought unwanted printed paper to wrap his wares from the stationers or at the old bookshops—as he read the text before he used the paper, 'in this way he had read through two Histories of England.'"

The largest amount of data in RED comes from the 19th century, an era richly represented in writings and archives. The archive is pushing beyond that period, though, as well as "internationalizing," Towheed says. RED projects have been established in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the Netherlands.

Edmund King, a research associate with the project, oversees the daily operations of the database. He joined RED in 2010 to hunt down references to World War I reading—a RED research priority, with the centennial of the conflict almost upon us.

"I've had quite a broad remit to go to various archives and libraries in Britain and basically read through letters and diaries and see what I can find," King says. He's amassed some 2,000 World War I records so far, which have already produced glimpses of reading in the trenches. Contrary to some stereotypes from the 1920s and 1930s suggesting that soldiers at the front were reading propaganda or jingoistic tracts, King says, "My sense of reading soldiers' diaries is that they were looking for something escapist, a reminder of home."

Families would send hometown papers to the boys in uniform. "Reading local newspapers was extraordinarily popular," he says. So was fiction that reminded them of childhood and let them escape, if only into the pages of a book. "Teenage adventure fiction becomes a big part of their lives."

Katie Halsey, now a lecturer in 18th-century English at the University of Stirling, also worked as a research fellow on the RED project. That stint led to a book, Jane Austen and Her Readers, 1786-1945 (Anthem Press), published this year.

Halsey wrote her dissertation on Austen. "I wanted to find information on her readers, and it had been incredibly difficult to do," she says. Before RED, "there was just nowhere to start."

"Nobody had been interested in that kind of thing," she says, "possibly because it was just so difficult to do" or because academe hasn't always cared what ordinary people said about books.

During Halsey's time at RED, a colleague gave her a tip about a Quaker reading group in Reading that had been meeting since the 1890s. "The fantastic thing about it was that they had kept written records of every meeting," Halsey says.

Studying the responses of Jane Austen's readers over 200 years confirmed what Halsey had suspected: "Janeites" tended to feel a great personal affinity for the author and "to build communities around her." The Quaker reading group did a dramatic reading of Austen the first time they read her, Halsey reports, and returned to her work over the decades.

RED's emphasis on recovering the experience of general readers has a lot to do with Simon Eliot, a professor of the history of the book at the University of London's School of Advanced Study. Eliot says he got the idea for RED 20 years ago in a car park in Coventry. He'd been to a conference on reading where most of the papers trained attention on a single, notable reader, he says. "I was worried that too much of our work was based on these rather anomalous, rather extraordinary, and therefore unreliable cases."

For every Pepys or Johnson or Woolf there were thousands of people just ... reading. Where were they? Eliot wanted to know more about what he calls "the reader on the Clapham omnibus." What, where, and how did the average Joe, however defined, actually read?

Of special interest were commonplace books, Eliot says, referring to the miscellanies or scrapbooks people often kept to help them remember intriguing or useful tidbits they'd read. Commonplace books were especially popular in the days when paper was still scarce and expensive, before a mid-19th-century revolution in papermaking technology caused manufacturers to switch to cheaper, readily available wood pulp. "Sometimes people just copied out huge chunks of a novel, because they couldn't afford to buy it," Eliot says.

The scholars involved with RED didn't want just lists of reading matter. "It wasn't enough to record a reading experience. We wanted to know where it took place," Eliot says. So they took pains to make sure the database record forms could capture other kinds of descriptive information about the reading experience. Did a reader's encounter with a book or newspaper happen in daylight or by candlelight? Was the book read out loud or in solitude? On the move or in bed? Eliot talks about a kind of punctuated reading dictated by stagecoach travel, in which a reader jolted along rough 18th- or 19th-century roads might snatch a few minutes with a book at inns whenever the coach stopped to change horses, kind of like how travelers now might read in the airport lounge before boarding.

National Library of Scotland

Soldiers in World War I, like these Australians in 1917, read hometown newspapers and adventure stories.

British newspapers have turned out to be sources of valuable information about reading circumstances and how they could turn deadly. "One account in the Times describes a woman in her bedroom, dressed for bed, reading a play, and the candle caught her hair, and she was found severely burned," Eliot says. "In fact it was suggested she wouldn't survive the day."

The play text found by the woman's chair was popular, budget-friendly reading material at the time: a kind of 19th-century proto-paperback, marketed to the reading masses long before Penguin came along. "They were usually 20 to 30 pages long," he says. "They were paper-covered. They would sell for sixpence, often as cheap as a penny or twopence."

Accounts of crimes sometimes include revealing details. For instance, Eliot mentions descriptions of pickpockets benefiting from the distraction of people "clustering around the latest poster" for a theatrical event. Such accounts, along with photographs and illustrations of Victorian cityscapes, and novels—Dickens describes paper blowing through the city—bring everyday experience back to life. "People in the 19th century are walking in a forest of print," he says.

That kind of "ephemeral reading" is exactly what people don't record in their diaries or commonplace books or in letters to friends. "Even if you're writing a quiet, secret diary, are you going to reveal that you spend time reading cornflake packets?" Eliot asks. "My guess is not."

One of the most vexing and intriguing aspects of studying the history of reading is how to recover acts and responses that were never deliberately recorded in the first place.

As a literary scholar, Leah Price is in the business of interpreting texts. In her latest book, How to Do Things With Books in Victorian Britain, Price cares not just about the content of books but how Victorians used them to create or control social relations. Books "can be used both as a bridge between people and as a wedge between people," she says. She turned to Victorian novels and stories to unearth evidence of how Victorians used books to woo and to repel. She also consulted nonfiction sources, including comportment guides, newspapers and magazines, and Mayhew's London Labour and the London Poor.

Price sketches out a broad, shifting range of uses for books that go beyond just reading. Because paper was expensive and therefore precious in early 19th-century Britain, people reused and recycled it. Books might be unbound and their pages used to make dress patterns, line trunks, or wrap pies. What began as text might end up as toilet paper. As a result, Price says, "even people who are illiterate for reasons of rank or sex still have a very sophisticated, fine-grained taxonomy of paper." Mayhew reports, for instance, that food vendors preferred certain newspapers because of the absorbent or repellent characteristics of the newsprint.

As texts circulated, they triggered class and social anxieties. An upper-class employer might worry that if she touched a book her maid had touched, she'd be sullied by the implied contact. "There have to be as many intermediaries between the master's body and the servant's body" as possible, Price explains. Think of the ritual of delivering letters on a tray.

After 1850, the rise of public libraries brought readers of different classes into closer contact. It set off debates about what reading matter was suitable for the public, Price says. Some libraries blacked out the racing pages of newspapers so as not to promote gambling, for example.

Victorians also worried about books as vectors of disease—"that question of where has that library book been," Price says. Proposals circulated for book-disinfecting machines to be installed at libraries. "It was mainly, if you pardon the pun, vaporware," she says. "But there were a lot of prototypes designed."

Easier access to reading material created other class-related strains, too, though not the ones Price expected. "I had expected, going into the project, that middle-class gentlemen would be worrying about their servants getting their hands on political tracts," she says. She discovered they were more concerned about time theft. Hours spent reading, even something like the Bible, were hours not spent dusting or doing other chores. Conduct books for women and girls, too, warned their readers against letting books distract from caretaking duties.

Sometimes employers inflicted unwelcome reading matter on their servants. A mistress might press a religious tract on her maid. "These are offers that you can't refuse," Price says. "One of the things that surprised me about the kinds of human relationships that are brokered by books in this period is that you see a pretty dramatic shift from the beginning of the 19th century." Early on, there was the sense that books were a precious commodity. By century's end, she says, there's a feeling "that books are something foisted or forced on inferiors by their social superiors."

Texts might be invitations to unwelcome contact, or markers used to define household boundaries. In romantic relationships, books played the part of matchmakers or match-breakers. "On the one hand, you have the book being used in courtship—a gentleman giving a copy to a lady that he's picked out for her, perhaps with certain passages underlined for her particular attention," Price says. "But on the other hand, you have the book as a wedge—the husband and wife who are ignoring each other at the breakfast table," one buried in her novel, the other in his newspaper.

In Anthony Trollope's novel The Small House at Allington, Price finds an especially harsh example of domestic distancing. Badly matched honeymooners, riding together in a railway carriage, feel more warmly about their reading material than they do about each other.

Trollope describes the scene: "He longed for his Times, but resolved at last, that he would not read unless she read first. She also had remembered her novel; but by nature she was more patient than he, and she thought that on such a journey any reading might perhaps be almost improper."

Victorians used texts to keep each other at arm's length in nonromantic spheres, too. With the spread of public transportation, "the newspaper grows up with the commuter rail as a way of avoiding eye contact," Price says. Like modern subway or bus riders losing themselves in their iPhones, 19th-century commuters could virtually escape the madding crowd by putting up a wall of paper between other people and themselves. "The Victorians were using books very much the way we use smartphones," as a kind of "Do Not Disturb" sign, Price says.

As the century wore on, paper itself became something to escape. "If someone is standing on the street corner handing out religious pamphlets, you don't want to take it," whereas in earlier decades you might have welcomed any free scrap of paper, Price says. She points out that, along with the shift from rag-based to wood-based papermaking, changes in the British tax system made paper much cheaper. That in turn made it more economical for publishers of books, newspapers, and pamphlets to print and sell their wares.

Reforms in the mail system midcentury also made it cheaper to distribute the new abundance of paper. The postal reformers "wanted to democratize knowledge," she says. But they "didn't foresee that this wonderful new postal system would be used primarily to distribute catalogs" and other ephemera. As Price says, the Victorians "really invented what we now call spam."

Echoes of Victorians' shifting attitudes toward text carry over into this era of digital reading. The 19th century had its cheap paper; we have ever more electronic content. As it did with the Victorians, abundance changes how we as a culture treat the physical book. For every bibliophile who worships the physical codex as an objet d'art, there's someone waiting to turn it to novel or irreverent purposes. Price points to the whimsical repurposings that turn up on sites like Etsy, as craftspeople turn books into purses and other objects with little connection to reading.

"There's such an increasing awareness today of nontextual uses of books," she says. "Now that the textual meaning of books is migrating online, all that's left is an empty shell."

Then as now, devaluing the object sometimes creates more emphasis on content. "Going back to the 19th century makes you realize that a phenomenon we tend to blame on digitization actually happened a century earlier," Price says. "Once you can throw it away, the value of books comes to reside in the words they contain rather than their potential for reuse."

Correction (12/18/2012, 11:11 a.m.): This article originally quoted Price as saying that Herman Melville owned a copy of The Natural History of the Sperm Whale that was pristine, indicating he had not read it. After the article was published, Price learned that the book had in fact been heavily annotated by Melville, and asked that The Chronicle replace her original example with the example of Hemingway’s copy of Ulysses. The article has been updated to add that example.

Jennifer Howard is a senior reporter for The Chronicle.

Art School Tells Students to Buy Pictureless $180 Art History Book

- by Kyle Chayka on September 18, 2012

What is this, October!? According to a blog post published by a disgruntled parent of a student, the Ontario College of Art and Design (OCAD) is forcing students to buy an art history book

for $180 — which wouldn’t be unheard of, but the catch is that the

publishers of this book didn’t get any of the image rights for the

artwork it includes. To reiterate, that’s an art history survey without

any pictures. WTF?

What is this, October!? According to a blog post published by a disgruntled parent of a student, the Ontario College of Art and Design (OCAD) is forcing students to buy an art history book

for $180 — which wouldn’t be unheard of, but the catch is that the

publishers of this book didn’t get any of the image rights for the

artwork it includes. To reiterate, that’s an art history survey without

any pictures. WTF?Instead of having pictures of artwork, the book, Global Visual and Material Culture: Prehistory to 1800 (so named for the course it goes with), instead just has placeholders with instructions to see a digital version for the actual image. It’s like a website with only broken image links. Just check out this hilarious sample page from the book:

An excerpt page from the pictureless textbook (courtesy ashleyit.com)

The disgruntled parent complains, “I’m not particularly interested in paying any amount for an imageless art history textbook.” We’re inclined to agree. In the context, OCAD’s faux-inspiring slogan of “imagination is everything” takes on a whole new meaning. Don’t have any pictures of art? Just imagine them all!

Thursday, December 27, 2012

The End of the Map

Apple Maps stands at the end of a long line of cartographic catastrophes. Say goodbye to the Mountains of Kong and New South Greenland—the enchanting era of geographic gaffes is coming to a close.

By SIMON GARFIELD

![[image]](http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/RV-AJ171_MAPSID_G_20121221183726.jpg) David Rumsey Map Collection

David Rumsey Map Collection

The Mountains of Kong, shown in

Africa on an 1839 American atlas, were 'discovered' by English

cartographer James Rennell in 1798. Rennell based his map showing the

fictional range on an erroneous account from a Scottish explorer. It

persisted on maps for almost a century—until it was discovered not to

exist.

As some may recall, it was not so long ago that we got around by using maps that folded. Occasionally, if we wanted a truly global picture of our place in the world, we would pull shoulder-dislocating atlases from shelves. The world was bigger back then. Experience and cheaper travel have rendered it small, but nothing has shrunk the world more than digital mapping.

![[image]](http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/RV-AJ163_MAPS_DV_20121221183535.jpg) Photo Illustration by Stephen Webster; Sebastiano del Piombo/Art Resource (painting)

Photo Illustration by Stephen Webster; Sebastiano del Piombo/Art Resource (painting)

There is something valuable about getting lost occasionally, even in our pixilated, endlessly interconnected world.

Maps have always related and realigned our history; increasingly, we're ceding control of that history to the cold precision of the computer. With this comes great responsibility. Leading mapmakers used to be scattered around the world, all lending their distinctive talents and interpretations. These days by far the most influential are concentrated in one place—Mountain View, Calif., home of the Googleplex.

There is something disappointing about the austere potential perfection of the new maps. The satellites above us have seen all there is to see of the world; technically, they have mapped it all. But satellites know nothing of the beauty of hand-drawn maps, with their Spanish galleons and sea monsters, and they cannot comprehend wanderlust and the desire for discovery. Today we can locate the smallest hamlet in sub-Saharan Africa or the Yukon, but can we claim that we know them any better? Do the irregular and unpredictable fancies of the older maps more accurately reflect the strangeness of the world?

The uncertainty that was once an unavoidable part or our relationship with maps has been replaced by a false sense of Wi-Fi-enabled omnipotence. Digital maps are the enemies of wonder. They suppress our urge to experiment and (usually) steer us from error—but what could be more irrepressibly human than those very things?

Among cartographic misfirings, the disaster of Apple Maps is rather minor, and may even have resulted in some happy accidents—in the same way that Christopher Columbus discovered America when he was aiming for somewhere more eastern and exotic. The history of cartography is nothing if not a catalog of hit-and-miss, a combination of good fortune and misdirection.

The map here, from explorer

Ernest Shackleton's account of his 1914-17 journey to the Antarctic,

notes the purported location of 'New South Greenland' (highlighted).

Described in 1823 by Capt. Benjamin Morrell, the island could not be

located.

These early scholars got a lot right—and inevitably a fair bit wrong. The map they constructed depicted the world as round, or at least roundish, which by the fourth century B.C. was commonly accepted (dismissing the Homeric view that if you sailed long enough you would eventually run out of sea and fall off the end).

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (in modern-day Libya) was one of the first scholars to marshal the new geographical knowledge into the art of cartography, making fullest use of the Library of Alexandria's scrolls, the accounts of those who had swept through Europe and Persia in the previous century, and the pertaining views of the leading contemporary historians and astronomers.

His world map was drawn in about 194 B.C., and the shape of the Victorian-era reconstruction of it (the original vanished long ago) resembles nothing so much as a dinosaur skull. There are three recognizable continents—Europe to the northeast, Africa (described as Libya and Arabia) beneath it and Asia occupying the eastern half of the map. The huge northern section of Asia is called Scythia, an area we would now regard as encompassing Eastern Europe, the Ukraine and southern Russia.

The map is sparse but sophisticated, and noteworthy for its early use of parallels and meridians in a grid system (with, bizarre as it seems to us now, the island of Rhodes—then a major trading post—at the center of everything). The inhabited world (something the Romans would later call "the civilized world") was believed to occupy about one-third of the northern hemisphere and was wholly contained within it.

The northernmost point, represented by the island of Thule (which may have been Shetland or Iceland), was the last outpost before the world became unbearably cold; the most southerly tip, labeled enticingly as Cinnamon Country (corresponding to Ethiopia/Somaliland) was the point beyond which the heat would burn your flesh. There are no poles, and the three continents appear purposely huddled together, as if the huge encroaching oceans and the vast areas of the unknown world are joining forces against them. There is no New World, of course, no China, and only a small section of Russia.

In the second century, the work of Eratosthenes would be one of the templates used to produce what is traditionally regarded as the bridge between the ancient and the modern world: Claudius Ptolemy's "Geographia." This contained a vast list of names of cities and other locations, each with a coordinate, and if the maps in a modern-day atlas were described rather than drawn, they would look something like Ptolemy's work, a laborious and exhausting undertaking based on a simple grid system. He provided detailed descriptions for the construction of not just a world map but 26 smaller areas.

As one would expect, Ptolemy still held a skewed vision of the world, with distortions of Africa and India, and the Mediterranean much too wide. But his projection of the shape of the world is still something we would recognize today, and the placement of cities and countries within the Greco-Roman empire is highly accurate. He gives due credit to another key source, Marinus of Tyre, whose map was the first to include both China and the Antarctic.

But Ptolemy was prone to the biggest and most contagious cartographic vice: Lacking precise information, he just made things up. Like nature itself, mapmakers have always abhorred a vacuum. White space on a map reveals ignorance, and for some this has always been too much to bear.

Ptolemy could not resist filling blanks on his maps with theoretical conceptions, something that plagues exploration to this day. The Indian Ocean was displayed as a large sea surrounded by land, while many of his measurements of longitude (something that was very hard to measure accurately until John Harrison's timepiece won a famous competition in the 18th century) were way off beam. The biggest miscalculation of all, the longitudinal position of the Far East, would eventually suggest to Columbus that Japan could be reached by sailing West from Europe.

But Ptolemy was at least attempting to map on scientific principles. Not so the wonderful mappae mundi, a collection of large conceptions of the world that filled our imaginations from the 11th century to the Renaissance. These maps, which primarily adorned the world's churches and other places of power and learning, succeeded in returning mapping to the dark ages, getting much wrong and gleefully so. Their goal was not navigation and accurate knowledge but rather religious instruction. The maps contained places we seldom see on modern charts these days—Paradise, for instance, and fiery Hell—and the sort of bestiary and mythical imagery one might expect to find in Tolkien's Middle-earth. We can marvel at the mythical bison-like Bonacon, for example, spreading his acidic bodily waste over Turkey, and the Sciapod, a people whose enormously swollen feet were said to make fine sun-shields.

The Renaissance and the golden age of exploration brought forth a stricter regime and hot-off-the-deck maps from Portuguese and Spanish explorers. Cumulatively, these resulted in the famous projection map of Gerardus Mercator in 1569, a plan of the world that still forms the basis of schoolroom teaching and Google Maps. The projection provided a solution to a puzzle that had troubled mapmakers since the world was recognized as a sphere: How does one represent the curved surface of the globe on a flat chart? Mercator's solution remains a boon to sailors to this day, even as it massively distorts the relative sizes of land masses such as Africa and Greenland.

The catalog of cartographic inaccuracies goes on. Those living in California may be curious to know that for more than two centuries their homeland was not attached to the West Coast mainland but was thought to be an island, drifting free in the Pacific. This wasn't a radical act of political will, nor a single mistake (a slip of an engraver's hand, perhaps), but a sustained act of misjudgment.

Stranger still, the error continued to appear on maps long after navigators had tried to sail entirely around it and—with what must have been a sense of utter bafflement—failed. Between its first appearance on a Spanish map in 1622 and its fond farewell in a Japanese publication of 1865, California appeared insular on at least 249 separate maps. Whom should we blame for this misjudgment? Step forward one Antonio de la Acensión, a Carmelite friar who noted the "island" in his journal after a sailing trip in 1602-03.

But my favorite cartographic error is the Mountains of Kong, a range that supposedly stretched like a belt from the west coast of Africa through half the continent. It featured on world maps and atlases for almost the entire 19th century. The mountains were first sketched in 1798 by the highly regarded English cartographer James Rennell, a man already famous for mapping large parts of India.

The problem was, he had relied on erroneous reports from harried explorers and his own imagined distant sightings. The Mountains of Kong didn't actually exist, but like an unreliable Wikipedia entry that appears in a million college essays, the range was reproduced on maps by cartographers who should have known better. It was almost a century before an enterprising Frenchman actually traveled to the site in 1889 and found that there were hardly even any hills there. As late as 1890, the Mountains of Kong still featured in a Rand McNally map of Africa.

And then there was the case of Benjamin Morrell, who had drifted around the southern hemisphere between 1822 and 1831 in search of treasure, seals, wealth and fame. Having found little of the first three, he apparently thought it amusing to invent a few islands en route. The published accounts of his travels were so popular that his findings—including Morrell Island (near Hawaii) and New South Greenland (near Antarctica)—were entered on naval charts and world atlases. In 1875, a British naval captain named Sir Frederick Evans finally began crossing some of these phantoms out, removing no fewer than 123 fake islands from the British Admiralty Charts. It wasn't until Ernest Shackleton's 1914-17 Endurance expedition, however, that the matter of New South Greenland was put to rest. Shackleton found that the spot was in fact deep sea, with soundings up to 1,900 fathoms. Morrell Island came off maps not long after that.

But perhaps we shouldn't be too hard on the early mapmakers, these pioneers of error. I would argue that Morrell and his misguided fellow adventurers made the world a more exciting and romantic place in which to live. Haven't we lost something important as mapmaking has become a science of logarithms and apps and precisely calibrated directions?

Though those who gratefully downloaded Google Maps on their smartphones last week might disagree, there is something valuable about getting lost occasionally, even in our pixilated, endlessly interconnected world. Children of the current generation will be poorer for it if they never get to linger over a vast paper map and then try in vain to fold it back into its original shape. They will miss discovering that the world on a map is nothing if not an invitation to dream.

—Mr. Garfield is the author of "On the Map: A Mind-Expanding Exploration of the Way the World Looks," to be published by Gotham next week.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

![[SB10001424127887323277504578191792854140524]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/OB-VT536_1221ma_D_20121220152352.jpg)